|

WorcesterThen: 1752-1916

Worcester High Schools, 1752-1916 |

|

In Worcester’s early years as a small courthouse town, most people felt little need for schooling beyond about age twelve or thirteen, the primary purpose being to learn a little reading, writing, and arithmetic. The main reason to continue beyond that age was to prepare for college, usually meaning Harvard, Yale, or Amherst, and the main reasons to do that were to become either a minister or a lawyer. The earliest form of a secondary, or “high” school was the Latin Grammar School, established in 1752, “for instruction in the languages.”*1 ( p.171). Located on Main Street at Mechanic, its purpose was to teach the Latin language and an introduction to its literature, and Greek and its literature as well, to prepare pupils for college. The term “grammar” at that time implied what would later be called “high” school, although it is not clear how the ages of the students resembled the norms of today. Higher education in those days was seen mainly as the study of the classics, the works of the Greeks and the Romans, upon which western civilization was considered to have been founded. A similar attitude prevailed in architecture, as can be seen in the predominance of classically-based styles such as Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival into the middle of the 19th century, and its off-and-on popularity ever since. In effect, culture and learning was defined during that era with reference to the classical ages of Greece and Rome. Aside: One of the early teachers at Latin Grammar was a young man from Quincy, and more recently Harvard college, named John Adams. The future president taught there 1755-58, apparently with a lack of enthusiasm for the task while he concentrated on his study of the law. [Wall]

The original grammar school was replaced, according to Wall, in 1789 by a new building on the west side of Main Street, which became known as the Centre School house. (p.185) Unfortunately, no images of these pre-photography buildings are known, at least to this essayist. Charles Nutt’s history of Worcester is another valuable resource on the subject, although it is sometimes difficult to follow.*2 In his discussion of colonial education, Kenneth J. Moynihan emphasized the Latin school’s existence as a product of the elite families concerned for college preparation for their male children.*3 Sources: *1 Caleb A. Wall, Reminiscences of Worcester, 1877. *2 Charles Nutt, History of Worcester and Its People, vol. 2 of 4, pp. 690-693. *3 Kenneth J. Moynihan, A History of Worcester, 1674-1848

About 1836 a new Latin School for Boys, including a “grammar,” or high school, as well as lower grades, was built on Thomas Street at Summer, the funds for it coming from the will of Isaiah Thomas. [Wall, Nutt] The grammar school pupils at the Centre School House moved into this building where they remained under the title of the “Classical and Grammar School” until 1845. The lower grades continued there, with the name changed to the Thomas Street School, until the mid-1950s. There was also something known as the Girls English High School, founded about 1824, but where it was located, how many students attended, and other matters are unknown. Neither Wall not Nutt made more than passing reference to it. Most likely it was a practical alternative approach to secondary education thought to be suitable for girls, for whom college was virtually out of the question. Its main purpose probably was the training of future teachers for the lower grades of school. The term “English” implied the use of the English language in classes, with less, or no, emphasis on Latin or other languages, and a wider, more diverse array of subjects. |

|

Classical and English High: 1845 At the town meeting of 1844, a resolution was passed establishing a school to be known as the Classical and English High School, open to “scholars of both sexes, and capable of accommodating at least seventy-five boys and one hundred girls.” [City Documents No.18 (1863), p.70] The new school was to serve boys from the Latin Grammar School on Thomas Street and girls from the Girls English High School. The fact that the school was to be for boys and girls together was of some significance. In a feature article on the school in a 1941 edition of the Sunday Telegram, emphasis was placed on the co-ed nature of the school. It’s headline read “Worcester’s First Co-ed High School Was Ultra-Modern Experiment In 1845.” [courtesy of Worcester Historical Musem] |

|

From the collections of Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

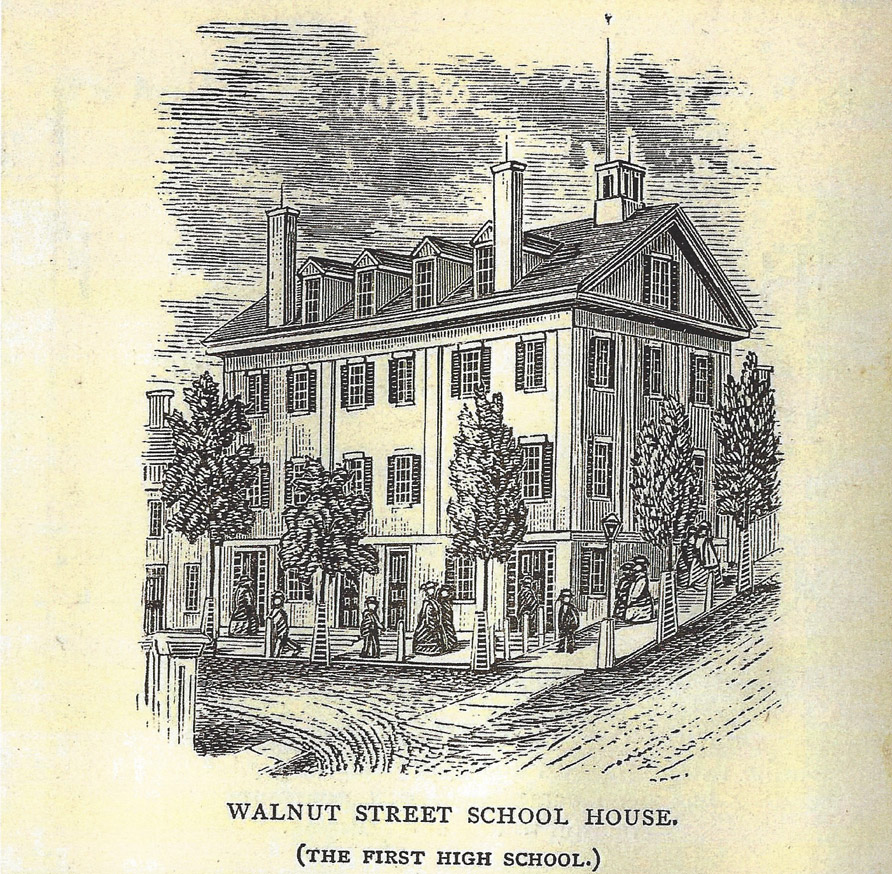

The name Walnut Street School House, as shown here, was used in its “second life,” after its relocation across Walnut Street, repurposed as a grammar school when a new and larger high school was built on the site in 1871-1872.

|

The building was erected between Walnut and Maple Streets on what came to be known as Maple Terrace. It was in the Federal style, made of brick, and measured 74 feet wide by 50 feet deep, with two stories plus a basement and an attic, and eight classrooms. In the original name of the school was a clear statement of the town’s decision to take advantage of both of the principal types of curricum at that time: classical, based on Latin and classical literature, and “English,” representing the wider array of topics considered to be essential to a general education not intended to lead to college, taught in English, with no particular reference to foreign languages.

|

|

The high school apparently had difficulties from the beginning. According to annual reports of the school department, enrollments varied considerably, always with a big decline during the school year,* but with year-to-year declines reaching a low of 77 pupils in 1854, after which the number began to increase. Problems, according to the superintendent, included high turnover of principals and teachers, yielding changing philosophies, and a lack of discipline and structure in the program. * The major reasons, according to various reports, were moving out of the city and quitting to go to work. In his annual report of 1863, the superintendent wrote that most of the dissatisfaction with the school pertained to the inadequacy of the English side of the two-part curriculum, which was by far the more heavily populated. Accordingly, the curriculum was revised as follows: “The Classical course was made to conform strictly to the requirements of Harvard College.” That continued a long tradition of “fitting” pupils to particular colleges, based on the expectations of those colleges for entering students, generally in regard to language proficiency and a level of familiarity with selectred classical literature. Regarding the “English” course, the superintendent said it had been made “more systematic and complete.” Some of the specifics provide a better sense of what they meant to accomplish in the evolving “English” program: Grammar and Arithmetic were stricken from the first year, requiring the Grammar schools to finish these studies. More time was assigned to History. The studies in Natural Science were placed in proper succession, - natural philosophy, chemistry, physiology, botany, or zoology, physical geography.” Also mentioned were courses in music and drawing “with the principles of perspective.” Somehow combined with this approach were paths for pupils wishing to prepare for the Normal School (preparation for teaching) or for work in commerce. |

|

|

A particularly important statement defining the nature of the Classical-English division was this: “Latin and French were made elective so that the purely English course would be complete in itself and entitle the scholar to the honors of graduation and a diploma.” Finally, the superintendent’s report offered some perspective on graduations and college attendance afterward. “The number preparing for college is never large. The records show that for several years past there have been but three or four each year, nearly all of whom have gone to Yale…. From the class of ’62, two went to Yale, one to Amherst, and one to Harvard.”

To what extent the situation improved is not clear, but in 1868 the average number “belonging to the High School” was 182, which was a relatively small increase over the 142 who originally enrolled. That amounted to a growth of 28 percent over nearly a quarter of a century, during which the city’s population grew by well over 300 percent. Even if the 142 number was exaggerated by counting those who started instead of those who stayed with the program, the numbers still leave the impression of a school that had struggled and failed to grow in step with the city.

|

|

|

Whatever the truth of the enrollment numbers, there was talk by the late 1860s of over-crowding and the need and desire for a new high school. A feature story in the Sunday Telegram in 1941 stated that “…only twenty-four years after its founding, this school was so pressed for space that the School Committee considered it prudent to have another house built as soon as possible.” A look at the school house shown earlier with the figure of 182 pupils, plus teachers, the principal, and the janitor in mind easily supports the conclusion that space was needed.

New facility The following year the decision was made to build on the site of the facility then standing. After visits to high schools in half a dozen New England cities, the Joint Standing Committee on Education solicited designs from architects, and settled on a plan prepared by Gambrill and Richardson of New York. The Richardson of the partnership was Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886), who became one of the pre-eminent architects of the era, known for his designs which became known as “Richardsonian Romanesque,” usually built of stone. The contract for construction of the school went to the Norcross Brothers, who recently had relocated to Worcester after completion of their first job in the area, the Congregational Church in Leicester (later destroyed by fire and replaced). |

|

|

Photo of photo, source unknown.

|

The association of the Norcross Brothers and H. H. Richardson forged in the Worcester high school project worked out well for both. In 1872, Richardson’s design for the Trinity Congregational Church in Boston firmly established his national reputation, and for its construction he secured the services of Norcross Brothers. A long and fruitful relationship followed, and after Richardson’s death in 1886 continued with the partners who inherited Richardson’s firm. Norcross Brothers became specialists in the construction of large, complex buildings of stone, and stone was the hallmark of the Richardsonian Romanesque style. They also maintained a close working relationship with McKim, Mead and White of New York.

|

|

The name Classical and English High School was continued with the new building, but in time it appears to have become known generally as “Worcester High School.” From its location only a block uphill from Main Street, the high school peered down on the core of the city,and was visible from many vantage points, especially its very tall tower, which rose about twice as high as the roof. The building footprint was 130 by 87 feet, and it was made of brick, with three stories plus a basement providing fourteen classrooms. And it was very much in the Romanesque Revival style of H. H. Richardson.

The 1845 building, still considered to be in good shape after a mere quarter of a century, was moved across Walnut Street to make room for the new building, and it served for many years as a grammar school for what today would be grades 5-8. It also served as the location of drawing classes at night. It was known as the Walnut Street School.

Over the next two decades the new high school served its purpose well, and total enrollments increased substantially. By the late 1870s a third course had been devised in the curriculum, called the “college” course – a rigorous classical approach to education, designed for pupils seeking entrance to Harvard or other elite colleges requiring concentration on Latin, Greek, and other languages. The “classical” course had diversified somewhat, and probably was aimed at pupils preparing for other forms of higher education, or possibly just an “old fashioned,” mostly-classical education at the secondary level. Here is a description of the three-course curriculum of 1878. Here is another worthwhile piece from the report of the superintendant of schools pertaining to the backgrounds of the pupils in the high school and the signicance of what he saw in the data.

|

|

By 1890 the average number of pupils “belonging” in the high school had risen to 778, an increase of 350 percent over the number in 1870. It is hard to imagine such a number of pupils in a building of fourteen rooms, since it means an average of 55 pupils per room. (Maybe they kept a percentage of them busy at each hour of the day with sports or physical exercise.) Needless to say, the time had come again to build another school. – a second high school, not a replacement.

One reason for the growth lay in the expanding purposes of the high school curriculum. In his annual report for 1890, Superintendant of Schools Albert P. Marble discussed the subject: “The purpose of the Worcester High School has always been two-fold: to fit for the higher institutions, the college, and to furnish an education complete in itself so far as it goes.” In other words, it was the “College” or Classical curriculum for those seeking entrance to college, and English for those wanting a more diversified, more practical education which would ordinarily cease upon receipt of the diploma. To these two long-standing courses of study the Superintendant said new needs had arisen, resulting in new purposes of the high school: “to give a special preparation for the Polytechnic Institute and for the Normal school, less extensive than the preparation for college.”

|

|

English High, separate from Classical High The new high school, to be built on land purchased by the city on Irving Street at Chatham, would be called English High School, and the not-so-old building on Maple Terrace would thereafter be known as Classical High. Worcester architects Barker & Nourse were hired, and their design was in the Romanesque Revival style, as was the senior building on Maple Terrace. The new edifice was completed in the Summer of 1892 and dedicated with the first class in September. |

|

|

Left: Photo of a photo in the Classical High Yearbook of 1931. (How the school came to be known as Classical High remains to be considered.)

Below: a more recent view

Google street view, 2015

|

|

The new English High building was made of brick, with three stories in parts and five in the tower section, plus a basement and a usable attic, providing a total of 22 rooms plus special function rooms, including a science laboratory and a gymnasium. The 1978 decription of the building filed with the Massachusetts Historical Commission called it “a superb example of Romanesque Revival style architecture, in an excellent state of preservation.”* This description still holds true as a result of the maintenance and concern for its historical significance by its owner, the City, and its tenant, Worcester Public Schools. It is known formally as the Dr. John E. Durkin Administration Building. * See Mass. Cultural Resource Information System, description filed by Worcester Heritage Preservation Society, now Preservation Worcester

During the 1890s, high school enrollments more than doubled in the city, rising to 1,650 pupils in 1900. This meant full capacity had been reached again after only a decade, and another high school was needed. In the early years of the decade enrollments were fairly evenly distributed between the two schools; in 1893 there were 522 pupils at Classical and 579 at English. For a few years, Classical had more graduates, but starting in 1896 English graduated more every year thereafter. Over time, the trend was toward the more diversified curriculum of the English course, including preparation for the Normal school and for the Polytechnic Institute (WPI).

Most of the growth in high school education in Worcester during this period was in the direction of the “English” curriculum. The classical approach to secondary education was far from dead, but the English approach was in the ascendant.

|

|

South High In the late 1890s the city made the decision to build a new high school in the fast-growing south Main area, on a site between Freeland and Richards Streets.

South High School opened in 1901, drawing its students on a district basis (unless they opted for the Classical curriculum at Classical and English), the first time districting had been used at the high school level. It opened with only 133 pupils, drawn from English High, but the next year it had well over 500, and the number later ran normally in the 700s.

(Note that in the peculiar directional skew of Worcester, “south” here is really southwest. Actual south would have been in the vicinity of Vernon, Millbury, Providence, or Ballard Street.)

|

|

Photo of photo in City Documents, 56, 1901

|

Goddard School of Science, contemporary Google view from Richards Street

|

|

South was designed in the newly-revived classical style, the era of the Romanesque having come to an end. It was made of brick with granite at the basement level, and stone was used for the quoins, lintels, and arches over the windows of the central sections of all four sides. This comparison of the old and the new makes it clear that, like the Administration building on Irving Street, South High has been conserved in its original state very well. The gymnasium in the contemporary view, which dates to 1931, was designed to match the main building.

In its curriculum offerings, South High was essentially another “English-type” school. The term “English,” however, was no longer needed and was not used. It was South High, not “South English High.” Thus the English-type curriculum had become the norm for high schools in Worcester. Classical High still existed on Maple Terrace, and it would continue into the mid-1960s, but its original primary purpose was beginning to fade. It, too, expanded and diversified its curriculum over the years, thus blurring the old distinction between classical and English. The modern high school curriculum had taken shape.

|

|

Trade Schools The establishment of Worcester’s Trade Schools, Boys Trade, 1910, and Girls Trade, 1911, is a worthwhile story of its own, one which deserves to be told, but not here. It was generally believed, at least by superintendants writing annual reports, that the trade schools drew mainly from young people who were not likely to be attending high school otherwise, so their effect on public school enrollments was minimal. The trade schools were in a special department of the city government under the supervision of a Board of Trustees. Its annual reports to the city were found under the “Department of Industrial Education .”

|

|

North High Despite a 23 percent increase in the city’s population during the first decade of the 20th century, enrollments in public day schools grew only very slowly – only 4.8 percent over the decade. Part of the reason was the expansion of the parochial school system, but only part. But if the numerical increase in pupils at the parochial and private schools is added to that of the public schools, the growth rate increases only to the range of 10-11 percent, still far short of that of the total population. It is unclear to this essayist why this slowdown in school growth occurred during the first decade of the century.

Despite the slow growth of total public enrollments, the three public high schools grew much faster – at about the rate of the population as a whole. High school enrollments gained about 22 percent during the decade, and this led to the need for another expansion of capacity -- another new high school. |

|

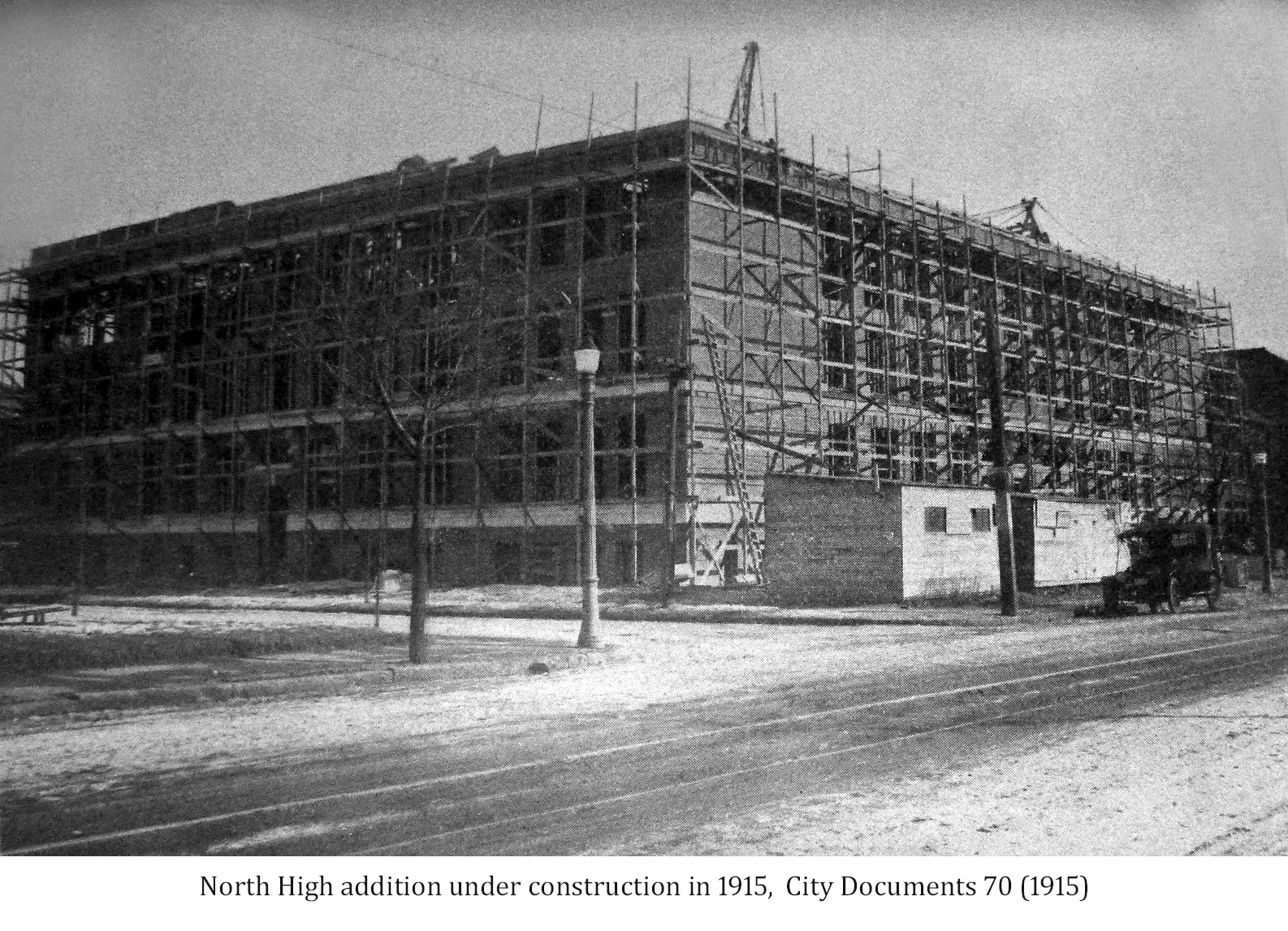

To meet the increased demand for high school “seats,” an elementary school on Salisbury Street, built in 1889 in the Romanesque Revival style, was converted to serve as the new North High School and opened with an enrollment of 327 pupils in 1911. In 1913, an extension of North High was opened in a former grammar school on Sycamore Street, with 142 pupils. It served the school’s overflow requirements until the addition to North opened in 1916.

|

North High,view from Lancaster Street (photo by author) |

|

North High under construction in 1915, from City Documents, 70 (1915).

|

North High Gardens, 2014, the addition of 1916 (photo by author)

|

|

Commerce High In 1914 the city adopted a plan for a new High School of Commerce, the purpose of which was to prepare non-college-bound pupils for work in business. Rather than build a new school, they put Commerce High in the Classical High building on Maple Terrace, and relocated Classical to the Irving Street facility. English High was terminated, its pupils distributed among the other three schools. The previous year a major addition to the Maple Terrace facility had been constructed next to the older building, approximately doubling the capacity of the school. Even with the additional space, the High School of |

|

Commerce opened in 1914 already overcrowded, with about 1225 pupils, plus about 225 from other schools who came for one or two classes, and had to use the facility on Sycamore Street formerly used by North High for “overflow” space. Enrollment at Commerce was about half again as large as any of the other high schools. In his 1914 annual report, the Superintendant described his view of the strong trend toward the commerce curriculum: “It is evident that it will be necessary soon to establish branches of this school in other buildings. The best plan may be to maintain first year classes of this school in the other high schools.” [City Documents 69, 1914, p.878] |

Source: Nutt, v. 2, p. 720

|

|

Approximately 45 percent of pupils coming out of the grammar schools opted for Commerce High, and girls comprised about three-quarters of total enrollment at the school. The immediate popularity of the High School Commerce showed the extent to which the movement toward high school education was directed toward practical matters of gaining employment in the commercial sector of the city. Subjects taught there included typing, stenography, bookkeeping, and elementary accounting. Thus, even the broader orientation of the “English” curriculum had not been as broad as the outlook of the high school age population. The success of the trade schools had also served as a demonstration of this fact. Classical High continued for another half century, apparently diversifying its curriculum somewhat, and lessening its focus on languages and classical studies. By 1920 its share of the high school population had shrunk to about 18 percent. |

||

|

Enrollment, Four High Schools, 1920 Classical 728 18.2 % Commerce 1,618 40.5 % South 730 18.3 % North 921 23.0 % Total 3,997 |

This was the status and composition of Worcester’s public high schools until the mid-1960s when a major round of changes broke up a pattern that had been stable for about half a century – from 1916 to 1966. In that year Commerce High was closed and the two buildings were demolished to make room for the Paul Revere Insurance Company, now UNUM, Inc.. Classical High on Irving Street was also closed after the 1965-66 school year, and the building was converted to serve as the main administration building for Worcester Public Schools. |

|

|

To replace the two that were closed, two new high schools were built: Burncoat High on Burncoat Street, which opened in 1964, and Doherty Memorial High on Highland Street, which opened in 1966. Neither bore the antiquated labels of Classical, English, or Commerce, or any other specialized approach to secondary education. |

|

|

|

Two main themes have emerged in the course of this essay. One is the gradual evolution of the curriculum of the high school system from the classical design oriented toward the most advanced scholars and their mostly elite families, toward a broader, more diversified and more practical curriculum aimed at a much wider segment of the population. This theme is in some ways the democratization of the city’s high school system.

The second theme, closely related to the first, is the increase in the proportion of high school aged persons attending high school. This is evident in the numbers of pupils entering and remaining in the high schools, yielding a higher ratio of high school pupils to all pupils. Gradually, the proportion of the high school-aged population of the city actually enrolled in the high schools, including parochial and private schools, as well as the Worcester Vocational-Technical High School, became much closer to full. Some data should help make this point and close the essay.

The increased tendency of pupils to attend high school (and for most to graduate) can be demonstrated by the proportion of all day school pupils who were in the high schools. Figures shown below are the numbers said to be “belonging” to the various grade levels of “graded” day schools between 1870 and 1930.

* City Documents for 1880 were missing from the shelf. The point is made well enough admitting this small deviation.

If there were equal numbers of pupils in each of the thirteen grades of school, including kindergarten, then the proportion of those in high school age would be four of thirteen, or 30.8 percent. Naturally, that would not likely happen because there would be some dropping out by older pupils, by and during high school, because of quitting to go to work, losing interest or the dedication required to finish, or because of any tendency toward greater rates of attendance at private or parochial schools among the older pupils. In this light, the nearly 27 percent rate of 1930 looks impressive, in fact, almost hard to believe. Perhaps there is more to the story that we don’t yet know. All topics of this nature remain open for further analysis. This essay is offered as an attempt to provide a primer on the subject, not an exhaustive or conclusive accounting.

|