WorcesterThen: early 20th century

|

Worcester Goes Wireless Don Chamberlayne January, 2018 |

|

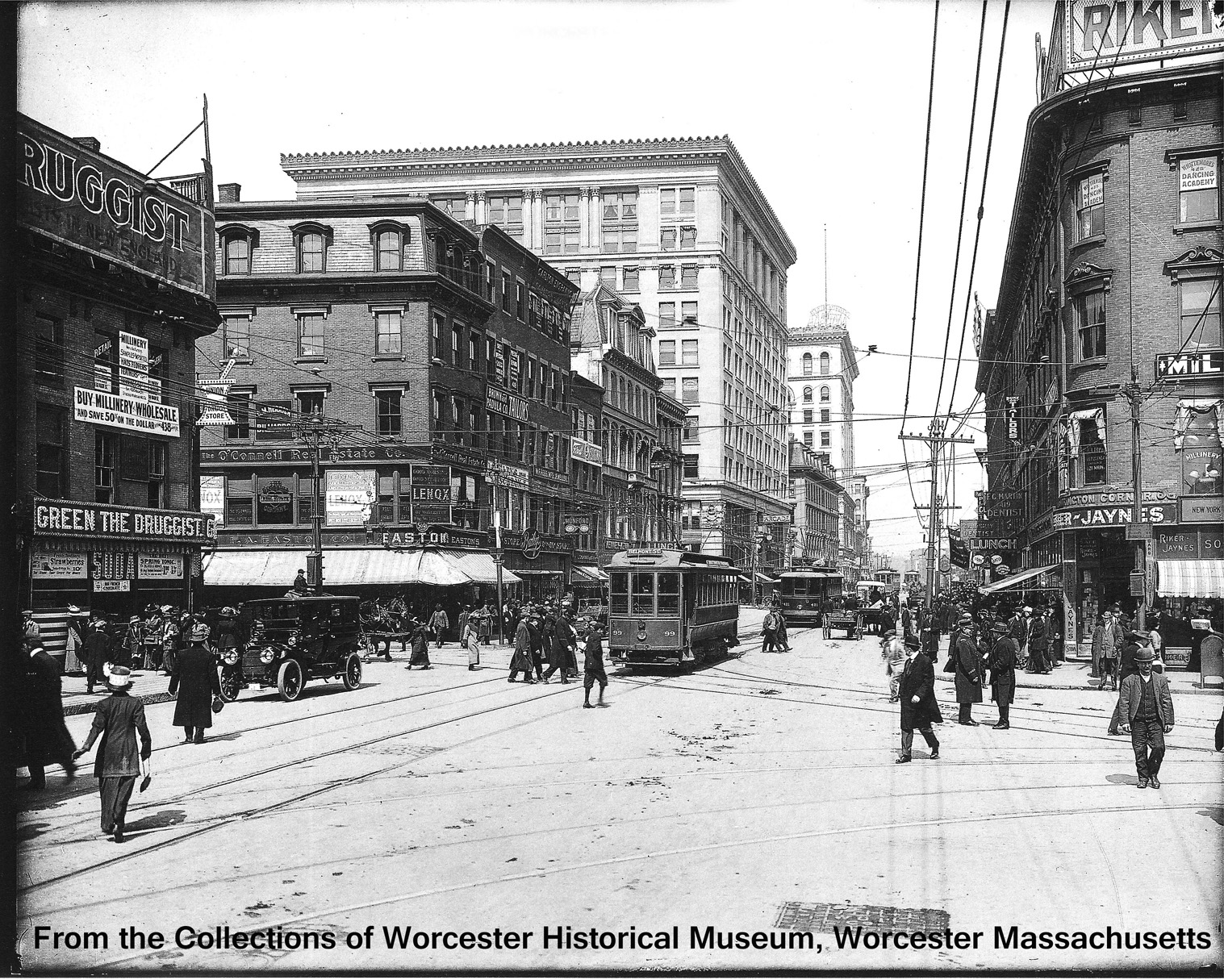

This photograph, from Picturesque Worcester by Kingsley & Knab, shows the intersection of Main Street with Pleasant and Front Streets at City Hall, looking northward up Main about 1894. For photo-dating purposes, the streetcars are running, although difficult to see (began 1893), and the State Mutual Building (construction began 1895) does not yet appear. Besides the buildings, some of which are still standing, and the bustle of pedestrians, take note of the tall and ungainly utility poles carrying a maze of wires overhead, most of which are barely visible in the picture. Poles on the far side of Main are extraordinarily tall, on the order of four stories, and the numbers of cross-arms, which are difficult to count, run close to 20 on each. |

|

|

Source: Kingsley and Knab, p. 13

(click on pictures for jpg images) |

Not all of the wires can be seen in the picture, but most of the cross-arms were carrying multiple wires – or soon would be. The products of those wires were electric power, telephone and telegraph service, and the fire alarm pull-box telegraph system. Though difficult to see, the “catenary” of the city’s new trolley, or streetcar, system consisted of high-power wires running above the tracks in the streets. In busy areas such as this “prime intersection” there were several tracks, straight and curving, and overhead wires were omnipresent. |

|

Whatever thoughts there were regarding their unattractiveness, these poles and wires must have seemed little price to pay for the great new benefits of the public transit system, electric lighting in the home (and more or less everywhere else), and the ability to talk with family or friends, the family doctor, or one’s coal dealer on the telephone. |

|

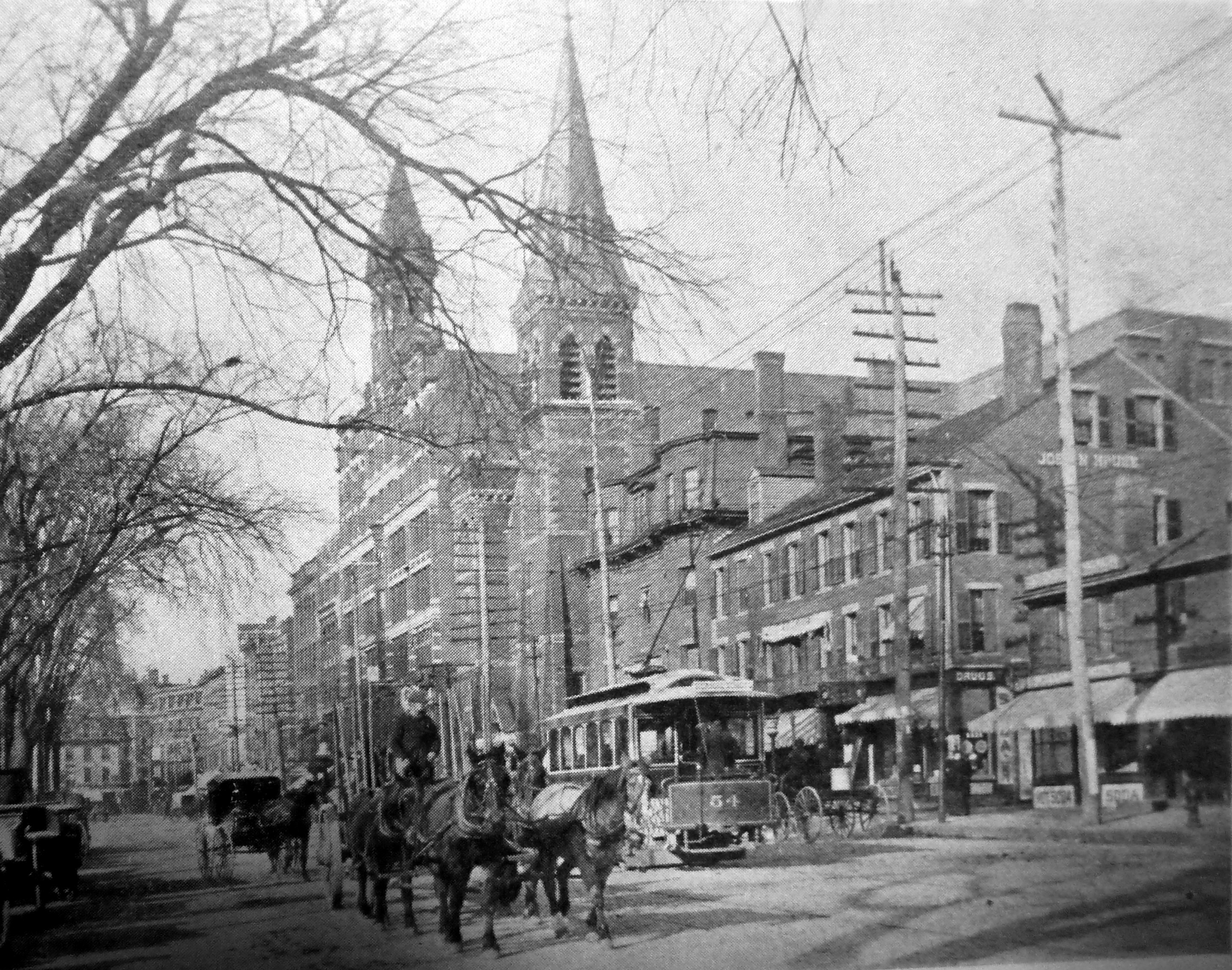

On Front Street approaching the railroad viaduct, ca. 1894, from Kingsley & Knab, p.6.

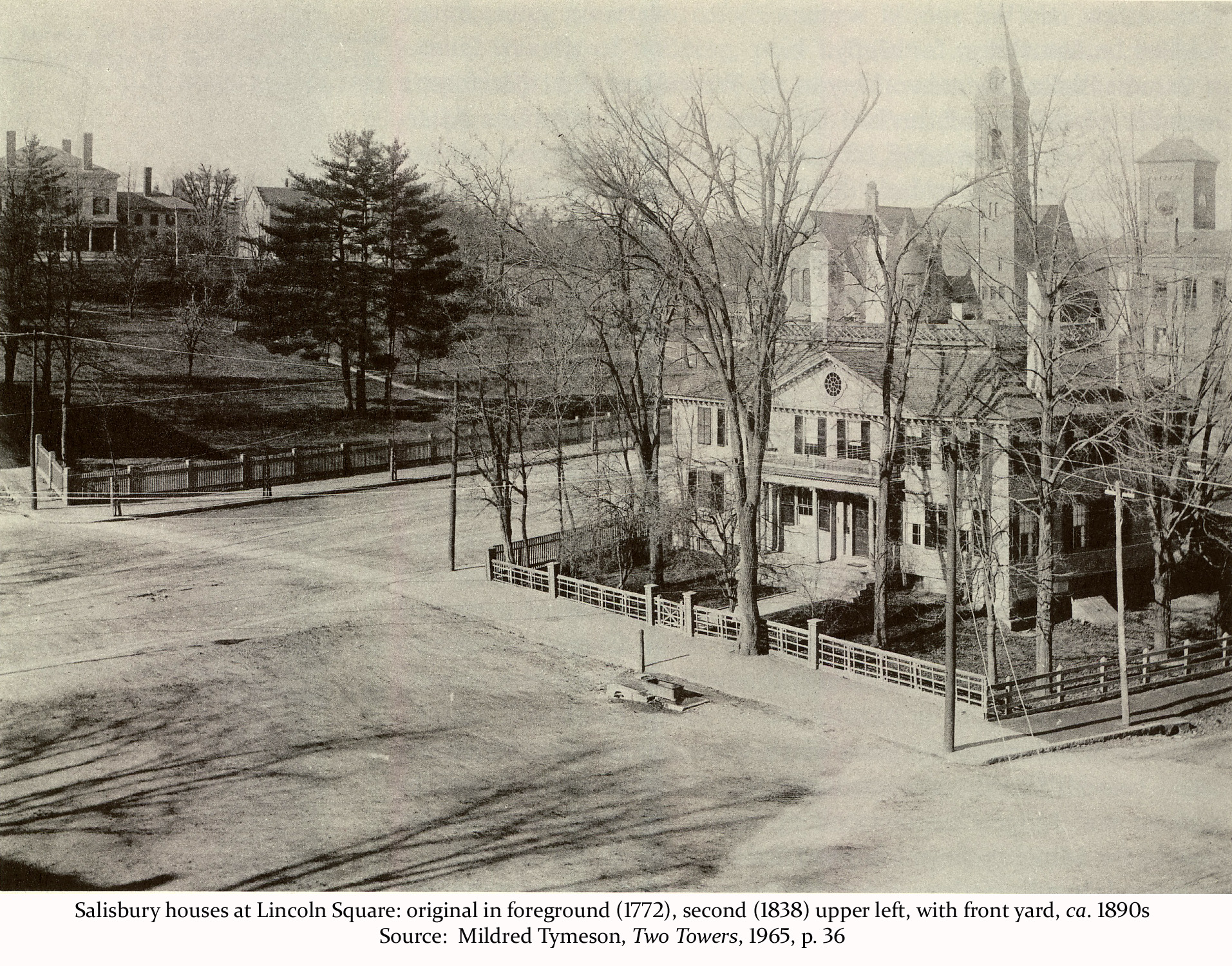

Lincoln Square Depot, 1890s, Kingsley & Knab, p.25 Nearby, a clash of the old and the new, or, from today’s vantage point, the old and the older:

The Salisbury mansion in the 1890s, with wires running across it on poles at either front corner of the property. (Source: Mildred Tymeson, Two Towers, 1965, p. 36.

Front Street, 1890s, from Kingsley & Knab, p.11 More tall poles, some bearing nine cross-arms. |

The initial wiring of the city began with the telegraph in the 1860s, was followed by the telephone and electric power in the 1880s and 1890s, and in the 1890s by the electric streetcar system. When these pictures from Kingsley and Knab were taken, most of this wiring had been strung during the past fifteen years or so, as telephone and electric power service joined the telegraph system as the principal components of the wired city. In its early days, electricity was thought of almost entirely as power for lighting, as there was little awareness yet of the additional uses of electricity which would later follow. Hence the prevalence of electric light companies and municipal power and light departments. Not surprisingly, it was about this time that talks began between the city and the various utilities responsible for all those wires about putting them underground. About 1894 discussions were held and agreements reached, and by 1896 all of the private utility companies responsible for the wires had begun the long and tedious process of replacing them with underground conduits. The work was being done on a voluntary basis by the Worcester Electric Light Co., the New England Telephone and Telegraph Co., the Western Union Telegraph Co., and the Postal Telegraph Co. The city must have had a major hand in guiding the design of the plan, but how it managed to obtain the agreement of the companies is unknown, as is the exact nature of those agreements. Starting in 1896, the city’s newly-appointed Supervisor of Wires gave a brief description of the progress of the project each year in his annual report. A few quotes from these reports should help one get “just enough” understanding of what was happening, including a little about the physical nature of the work involved. From the report of Supervisor Henry A. Knight for 1896: The telephone company has drawn a considerable amount of wire into their conduit during the year, and has made corresponding reduction in the number of its overhead wires, 28,954 feet of cable, representing 308 miles of single wire, and about 116 miles of open wire on Mechanic, Main, Pleasant, Elm, Trumbull and Beacon streets, having been taken down during the year.

The company had laid about 5.5 miles of cable, consisting of numerous strands of small-gauge wire, bound in a sleeve, which would replace some 308 miles of wire carried by poles. This implied that there were about 60 pairs of wires in a cable, each providing telephone service for a “line,” which might have been a “party line” of two or more customers sharing a line. |

|

To date, 116 miles of open wire had been taken down upon the opening of underground cables. In order to minimize “down time” for phone service, the open wires could not be taken down until the cables running through the conduits had been rendered fully operational. Wire used to carry electricity was subject to much more demanding requirements than was phone wire due to the high voltage and current (electric power) being conducted through it, which resulted in heat and conductivity issues. Finding a suitable wire held up their progress for a period. Supervisor Knight, in 1896 again: The Worcester Electric Light Company have, after many experiments, found a wire which is considered suitable for their use, and intend to begin running wires in their conduits in the early Spring. (It must have helped to be operating in the home city of the Washburn & Moen wire company, which presumably turned out the wire as fast as the utilities could put it to use, and with the benefit to the local utilities of minimal transportation costs.) The conduits consisted of clay pipes, connected securely to each other, with curved sections for horizontal or vertical turns, as required, containing a bundle of ducts, typically numbering between four and twelve, bound together by concrete, the whole of which was buried in concrete. The Supervisor again: The conduit used in this work is vitrified clay, with dowel pins in each section to secure perfect alignment, and the whole imbedded in concrete, making practically a solid stone, with ducts running longitudinally through its entire length. One duct in each conduit is reserved for municipal purposes. (1900, p. 6) |

|

By 1898, New England Telephone & Telegraph had buried its lines throughout the downtown area and in some nearby residential areas as well. In 1899, the Supervisor of Wires wrote that he expected to see during the coming year all overhead electric wires removed from the central city area, as well as the burial of remaining telegraph lines. “With this accomplished, the only overhead construction remaining in the centre of the city will be that of the street railway, the long distance telephone, and that of the automatic fire-alarm people” [a telegraph system operated by call boxes]. The commissioner’s annual report for 1900 said the Electric Light Company had constructed during that year eleven miles of conduit containing four-to-twelve ducts, and that it had taken down 43.6 miles of wire during the year. Thus, by the turn of the century most of the overhead wiring in the central part of the city had been replaced by underground wiring in conduits. The visual effect was great, as can be seen below in the well-known E. B. Luce photograph of the prime intersection in 1910. Electric and telephone lines having been removed, the streetscape was much less cluttered than it had been in the 1894 scene shown earlier, but wires remained for long distance telephone and the call box system, and the poles needed to carry them, as well as the trolley power line catenary. |

The prime intersection again, in 1910:

|

|

|

From the E. B. Luce collection of the Worcester Historical Museum. This image is a scan of a card mailed out by the Museum in 2014. The quality is not the same as would be if provided directly by the Museum. There are still some poles and wires, but nothing like the early 1890s. Note the Slater Building and the State Mutual Building which have risen on the street since the previous picture of this same location. |

|

Going off theme just a bit… Traffic at that early stage in the coming of the automobile was a chaotic blend of cars, trolleys of varying sizes, including the largest of them known as “battleships,” plus horse-drawn wagons, bicycles, and pedestrians, and even a few dogs. There were few if any rules of the road by this date. People meandered in every direction, winding their way through the traffic, the motorized part of which was supposed to keep within the speed limit of 8 mph, and horses pulling carts and carriages were becoming accustomed to negotiating with the new motor vehicles which would soon reduce their workload considerably. Recommended: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YRbMMqj0qw A Trip Down Market Street, San Francisco, 1906 , Youtube Video, 00:12:17, with sounds from the street. This film offers an unmatched sense of life in city streets at that time. San Francisco was a bit larger than Worcester, of course, and had a lot more automobiles, but essentially the scene here should have been comparable on a smaller scale. The film was made four days before the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. If you decide to exit the film early, be sure to skip to the last minute before doing so.

|

A similar but slightly different Luce photo, same place, same day:

|

From the E. B. Luce collection, courtesy of the Worcester Historical Museum. |

Here the streetcars are more visible, as are their tracks and, just barely, the overhead power wires. The one automobile in the picture was a fairly fancy and no doubt expensive one, and a close-up view reveals that the steering wheel was on the right side. Apparently the American custom of driver on the left, traffic to the right had not yet become established. |

Some other street scenes after most but not all wires had been removed from the downtown area:

|

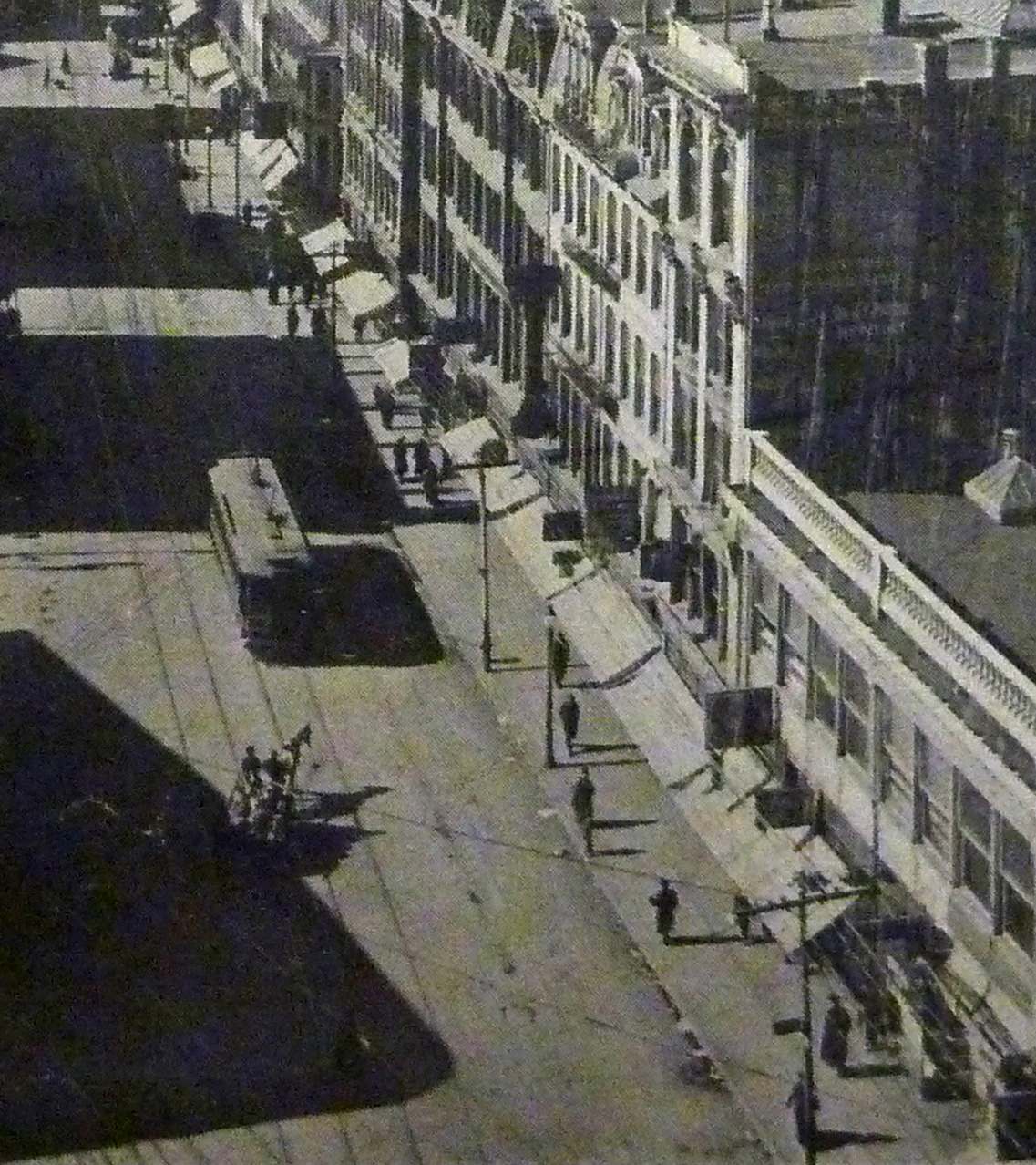

Main Street looking south from the Park Building, ca. 1915

Worcester Magazine, 1915 detail of a larger image used in the magazine. Note the line of poles with one cross-arm each, carrying a half-dozen or so wires. It was not yet “wireless” but it was a long way from the 1890s before the change to conduit. |

The Dodge building on Franklin Street, 1910s

From the collections of Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Ma. The Dodge building on Franklin Street at Portland, across from the Bancroft. It later was merged with the Sawyer building next door, and in 1961 a fire destroyed the mansard roof and floor. The door nearest the car on Franklin Street was added in the early 20th century in the physical merger of the two buildings. Here overhead catenary runs over tracks in Franklin Street, and crossing wires make a long stretch to the pole a block down Portland Street, about 300 feet, per Google Maps measurement. |

* * *

|

Despite all the progress that had been made by the turn of the century, there apparently arose some limit to what could be achieved under the voluntary arrangement. There may have been some level of disagreement between the city and the companies, possibly over the direction, speed, or extent of the operation, because the matter in 1902 became an issue for the consideration of the state legislature. The most likely reason for the city’s decision to go the legislative route, thus ending the voluntary nature of the program, pertained to the distance out from the center that was to be covered under the program. The voluntary arrangement tracing to the mid-nineties had an agreement for a one-mile radius. Now the city wanted a two-mile radius, which would multiply the area of coverage by four. The legislative process called for a hearing before a committee in Boston, and one would expect to find that there was some degree of disagreement surrounding the issue, and that the story was covered in the press. But a search through two city newspapers, The Spy and the Telegram, a week before and a week after the legislature’s action on the request in early May, yielded no coverage at all of the matter. The issue might have become a non-story as a result of some prior agreement. On May 6, 1902, the General Court enacted Chapter 372 of the Acts of 1902, enabling Worcester to adopt an ordinance to put the terms of the legislation into effect, which it did on January 3, 1903. To execute the program authorized by the Act the new Commission on Wires and Electrical Appliances was established, consisting of the City Engineer, the Street Commissioner, and the Supervisor of Wires. The new ordinance affected the electric and telephone companies, but had little if any effect on the telegraph companies, since their lines were run mostly to newspapers, banks, brokerages, and store-front telegraph offices located in the business center. Long distance telephone lines were given exception from the underground requirements, provided they ran at least 25 miles outward from the central office. They usually ran along railroad rights-of-way and vehicular roads.

|

|

For the telephone and electric power providers, the extension of the range to two miles meant an additional 9.45 square miles of coverage, the original amount of surface area repeated three times again, although with somewhat lower density of use. The additional coverage would not be as difficult or as expensive for the companies as had been the project in the downtown area. Besides the additional area being less densely developed than the business district, the plan for extending the coverage did not call for abolition of poles and wires but instead to use them extensively, but located along the backyard lines of properties on the blocks, not along the streets. Thus, the wires branch from poles to the houses by way of their backyards, not from the front. In his annual report for 1902, the Commissioner of Wires (dated January, 1903) wrote that… “It is understood and admitted that the companies must have distributing poles to furnish outlets from their conduits to their customers, but these distributors should be so located as to carry the service wires on the back lines of house lots rather than along side streets.” At key locations behind the properties along the streets, wires were to emerge from the underground conduits, run up utility poles inside protective sleeves, and then run from pole to pole until the end of the line, serving properties along its path. The poles were to be owned by one of the utility companies with space leased to the other, and electric power, because of the danger factor, was always to be at the top, with low-power telephone lines running well below them, a practice still followed, now with TV and internet cable also running low, near the telephone lines now called “land lines.” It is not clear whether the poles which started the runs had or have a name in the trade, but here they will be called simply “first-poles.” |

|

A first-pole, as shown below, has protected wires coming out of the ground and running up the pole, with overhead lines beginning there and running down the backyard lines of a block in a covered area, or down a street if outside the two-mile limit. Usually, guy wires are necessary to relieve the stress on the vertical positioning of the pole due to the force of wires running in one direction without being balanced on the other side, a problem which is more severe in storms from the weight of ice or the force of broken or thrashing tree limbs. |

|

The first-pole on Coburn Avenue, off Belmont Street, an example of a first-pole on a street outside the two-mile limit. Where Coburn “tees” into Belmont Street is outside the two-mile limit, but Belmont has no poles or overhead wires all the way to the bridge at Lake Quinsigamond.

The other kind of first-pole is the one at the end of a neighborhood block nearest the area’s conduit line, as shown to the right. |

The Google streetview below is from Highland Street across a parking area which allows a view of the first pole of the block between Sever and Roxbury Streets. Beyond the pole to the left are the Worcester Tennis Club courts. Wires run down the block behind the courts but also leftward(easterly) to provide land-wire services (electricity, telephone, and cable) to the brown house and to another pole, out of sight here, which is required to serve the two buildings on Highland connected at the front by Bonardi’s (formal wear).

|

|

The idea of the plan to bury the wires was not to have no overhead wires within the two-mile limit but to have no overhead wires along the streets within the limit. Conduit was to run underground along arterial streets and certain others which veered off from the arterials, and at various points along the way to dispatch branch conduits off to either side, leading to “first poles” where the wires would come up for an overhead run along a series of poles. All customers receive service by way of overhead wires, not, directly, the underground conduits. Arterial streets are those which run outward from the center, and which carry traffic in and out of the center of the city. Sometimes they connect to other arterials on the way in or out, such that one does not reach the center of the city. Two examples, coming inward, are Burncoat Street which feeds into Lincoln, and Massasoit Street which feeds into Grafton. First-poles can be found on West Boylston, Burncoat, Lincoln, Grafton, Massasoit, Vernon, Providence, Millbury, Main, Stafford, Mill, May, Chandler, Pleasant, Salisbury, and Grove Streets, and possibly some others as well.

|

|

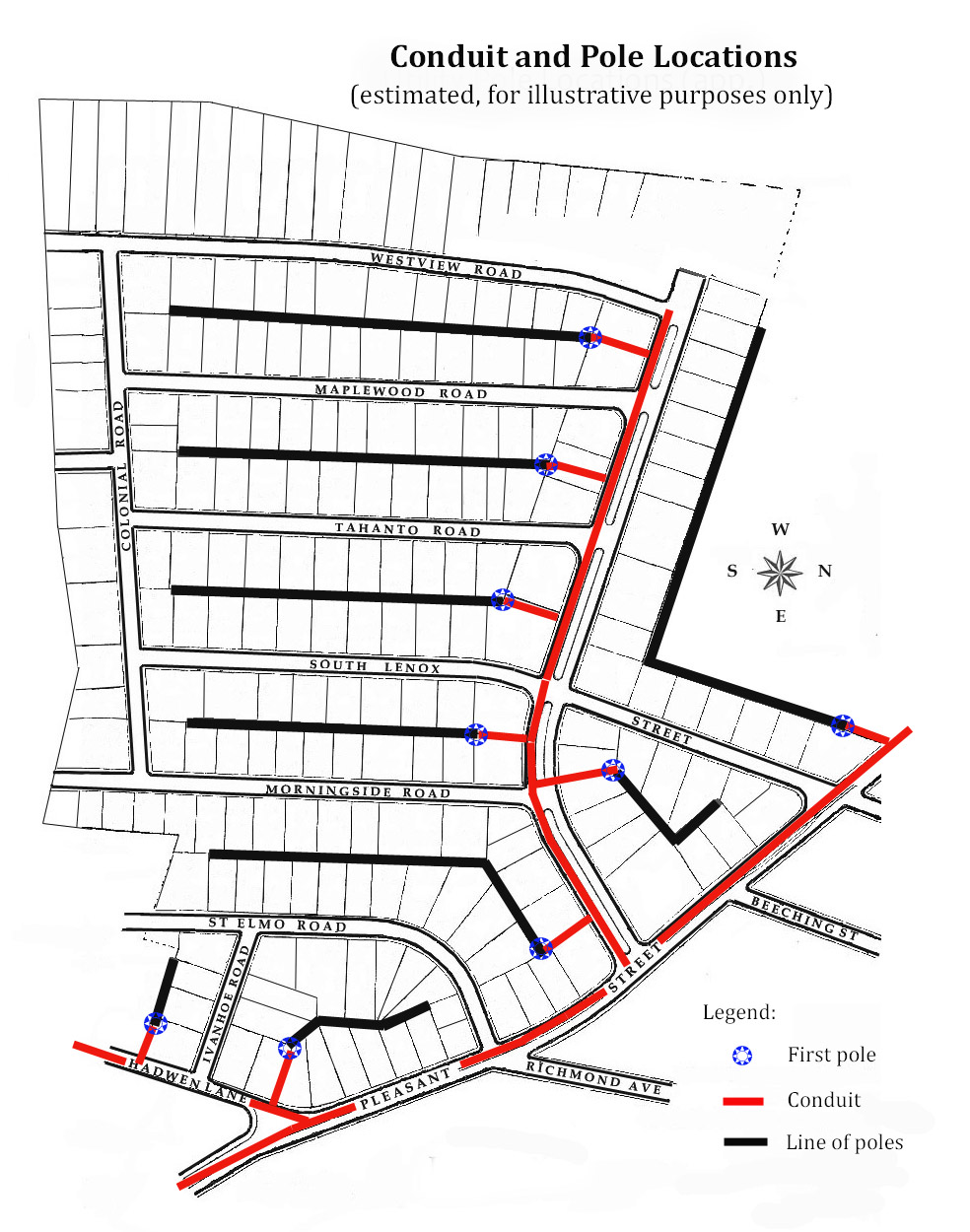

A prototypical street plan for conduit and wires may help to firm up the idea. Here we use the street plan for Lenox, a subdivision along Pleasant Street (within the two-mile limit), approved by the Board of Aldermen in 1910. |

|

|

To see the image more clearly click on the map. |

Please note that the “wiring diagram” shown here is the author’s best guess as to how the conduit might have been laid out in Lenox, and it is not necessarily accurate and, in fact, probably is not. But it doesn’t have to be accurate to make the point, which is that something like this configuration was, and remains, the case, and that it stands as typical of the way the underground wiring scheme works.

The underground conduit runs outbound along and under Pleasant Street and has connection points (requiring manholes) at Hadwen Lane and Chamberlain Parkway, where branch conduit runs under those streets, and sends conduit spurs to the various first-poles of the blocks. From those points, poles and overhead wires distribute service to the customers on the block. |

|

The replacement of overhead wires with underground conduits was a task of very major proportions. It seems safe to say that it was considerably more complex than had been equivalent lengths of water or sewer piping, and undoubtedly it was more expensive on a linear-foot basis because of the complex nature of the conduit and its various ducts, as well as the wiring itself. It was not, however, necessary to construct anywhere near the length of underground conduit for electric or telephone service that was required of the piping of water or sewage. Nevertheless, the placement of wiring underground was a very big and expensive operation. It should be taken into consideration that the telephone company would eventually have had to take down the overhead wires and replace them with cable anyway, so the cost of doing that should be seen as offsetting part of the cost of the conduit job. From the city’s adoption of the ordinance in 1903, the project was one of covering the nine-plus square miles of the second ring, the areas within the two-mile limit which had not been done yet. Each year, in the Wire Commissioner’s annual report, he stated the numbers of poles and the miles of wire that had been taken down that year by the telephone and electric companies, but there was no summation of the numbers of poles or miles of wire taken down at the end of the project. It was not until 1936 that the last mention of poles and wires coming down appeared in the annual report. Thus from the initiation of the voluntary project in the mid-1890s it had taken forty years to finish the task. Whether that was as long a time for such a project as it seems to have been, from the vantage point of a later age, it did manage to take that long. Why it took so long doesn’t seem important, and in any case the answer is beyond the scope of this essay. For an approximation of the total number of poles and the total mileage of wire taken down, a sample consisting of all that could be found during the voluntary period, plus a one-in-three sample of reports between 1903 and 1936, yielded a rough estimate of about 6,000 poles and some 1,500 miles of overhead wire taken down. By the late 1920s long-distance telephone lines had also been buried, and the Fire Alarm telegraph system had converted to underground conduit and cable similar to that used by the telephone company. The result, with only a few relatively minor exceptions, was the total elimination of wires from streets within the two-mile limit of the prime intersection at City Hall.

|

|

|

Here is the prime intersection at City Hall again, this time as seen from the camera of the Google Streetview system in 2016.

Gone but not forgotten are the poles and wires which once dominated the view.

|

|

|

Another recent Google photo, taken at the intrsection of Front and Foster Streets, with the viaduct and Union Station in the background. No wires are to be found. Poles are for flags, street lamps and traffic lights. |

|

The absence of poles and wires in downtown areas of cities is now common – probably the case in the vast majority of cities. What distinguishes Worcester is that it accomplished the task so early and that it did it so extensively. The most common municipal approach to the problem has been to confine the costly task to the central business district, and selected areas off to the side of the CBD, such as highway interchanges, water-side parks, and other public attractions. Worcester, however, covered an area of a two-mile radius from City Hall, about twelve and a half square miles. This essayist, for one, feels that the result has been a major and important achievement for the city, one that makes the surroundings far more attractive to the eye and more conducive to viewing the varied architecture and landscaping of the city’s neighborhoods. A few of the first-poles found on some of the radial streets of the city are shown below. |

|

Main Street near the Leicester line:

|

The first-pole on Main St. is well beyond the two-mile limit, which comes just before Webster Square. In fact, it is almost all the way to the Leicester line, at the Kettle Brook Lofts apartment complex (a former woolen mill). Why this is the case is unknown to this compiler. Wires from this pole cross Main Street first, then head westward into Leicester. Google Streetview, image dated 2011 |

|

Stafford Street:

|

The first-pole is at Moe’s restaurant, just beyond Webster Square. The streets between Stafford and Main, such as Grandview Avenue shown below, all have poles and wires along the streets, not in the back yards.

All photos in this section are Google Streetviews. |

|

Grandview Avenue

… on Grandview, a normal run of poles and wires, outside the two-mile limit. Note the canister near the top of the pole. A detail of it is at the right. Both pictures are Google streetviews. |

The canister, or tank, is a step-down transformer, which decreases the high voltage carried in the wires (those at the top) down to 120 volts A.C. for normal residential use. The circuitry inside the tank is immersed in oil for purposes of cooling and more efficient use of paper spacers between the windings. |

|

Inside the two-mile limit: Main St. at Hancock:

… no poles or wires, except for a street light pole |

… and Florence Street:

Above the silver colored car in the parking lot can be seen (barely) a backyard pole. |

|

||

|

Burncoat Street, just beyond Clark Street.

|

Monterey Road, in the Maplewood area off Burncoat Street, inside the two-mile limit

|

|||

|

Pleasant Street entering Tatnuck:

On Pleasant Street the first-pole is in front of the Tatnuck School (off-screen to the right), and the wires cross Pleasant in two directions, one of them heading down Mill Street.

|

Massasoit St., 200 block, a little past Fenwood:

|

|||