|

WorcesterThen: 1876-1950s

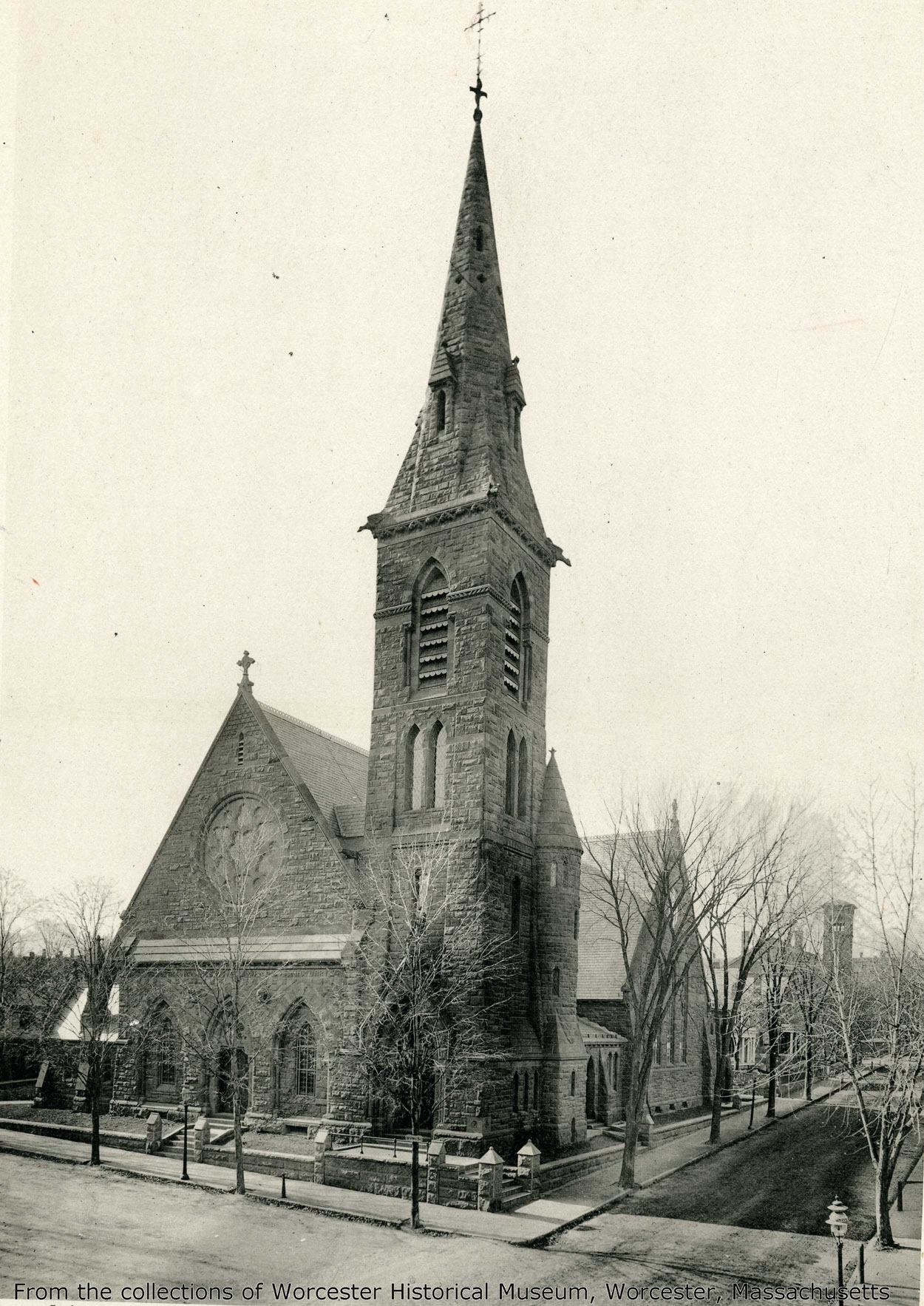

The All Saints Episcopal Church |

|

Papers filed in 1836 established the “Protestant Episcopal Church in Worcester,” a local component of the “Protestant Episcopal Church in America,” which can be thought of as a “nephew,” or first cousin, of the Church of England, or Anglican Church. There is a touch of irony in this in that the Anglican church had been the target of the wrath of the Puritans, who had emigrated to America to break free of it, and who formed the greater part of the founding population of Massachusetts. A good percentage of the earliest settlers and their descendants became members of the Congregational church in New England. But at the time this Episcopal church was being organized in Worcester, two centuries had passed and most of the steam had gone out of the issue. Please note: This essay does not purport to convey the history of the Episcopal Church of Worcester, or the All Saints Church specifically. It is merely an outline of certains events involving the physical structure of All Saints. No attempt was made to contact members of the church or to examine its records or collection of historical documents. The holdings on the subject of the Worcester Historical Museum were consulted, however, and several photographs from it are incorporated in the essay. The original Protestant Episcopal Church in Worcester, All Saints, was located on Pearl Street on the site of the former GAR hall. The wooden structure was enlarged in 1860 and was altered on three occasions after that, but then was destroyed by fire in 1874. |

|

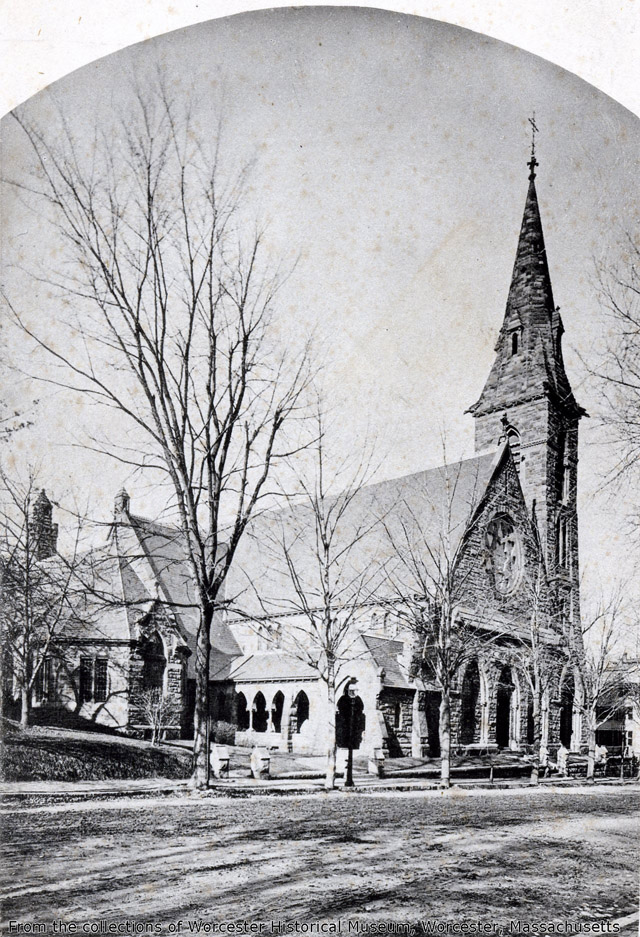

Seeing a need for more room for future expansion, the church opted to rebuild not on the Pearl Street site but on Irving Street at the corner of Pleasant. The new building was designed by Worcester’s foremost architect of churches during this period, Stephen C. Earle, and it was constructed by the Norcross Brothers, who by this time were well on their way to national pre-eminence as builders in stone. Construction was completed at the end of 1876. Architecturally, the new building was primarily of brownstone, in the Gothic style, characterized by pointed arches, and having trefoil shapes within the arches. It had entances at the tower and the central doorway was at the front, on Irving Street, with windows on either side.

|

From the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts (1910) |

||

|

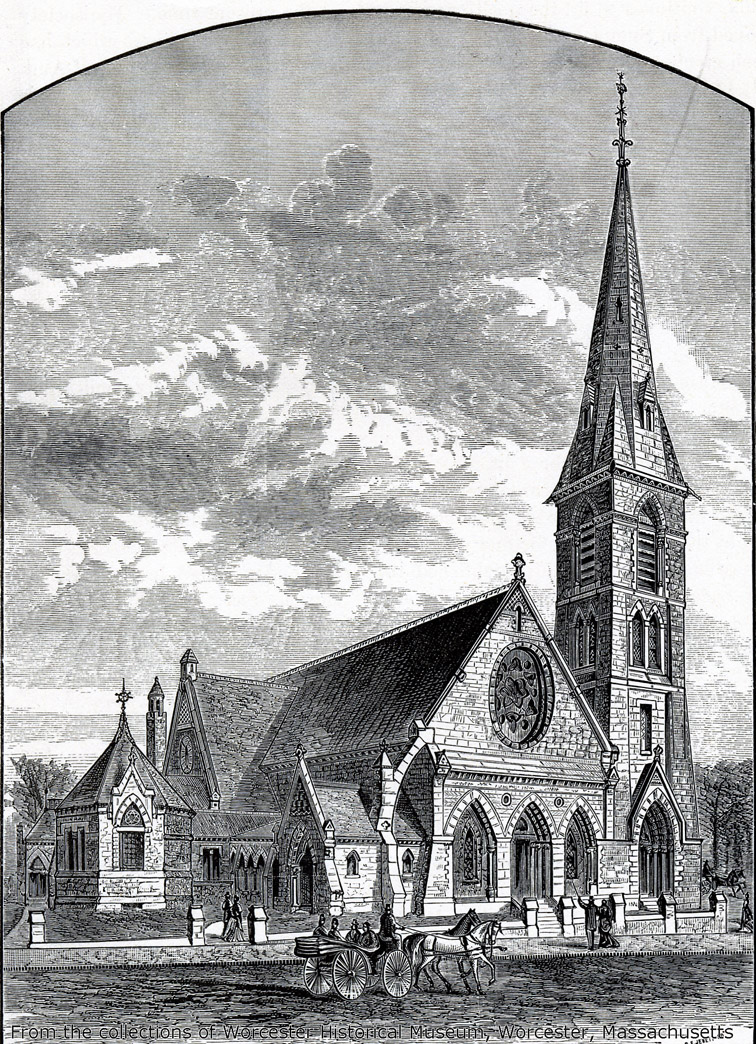

From the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

This early (undated) engraving or lithograph shows details more clearly than does the photograph above.

|

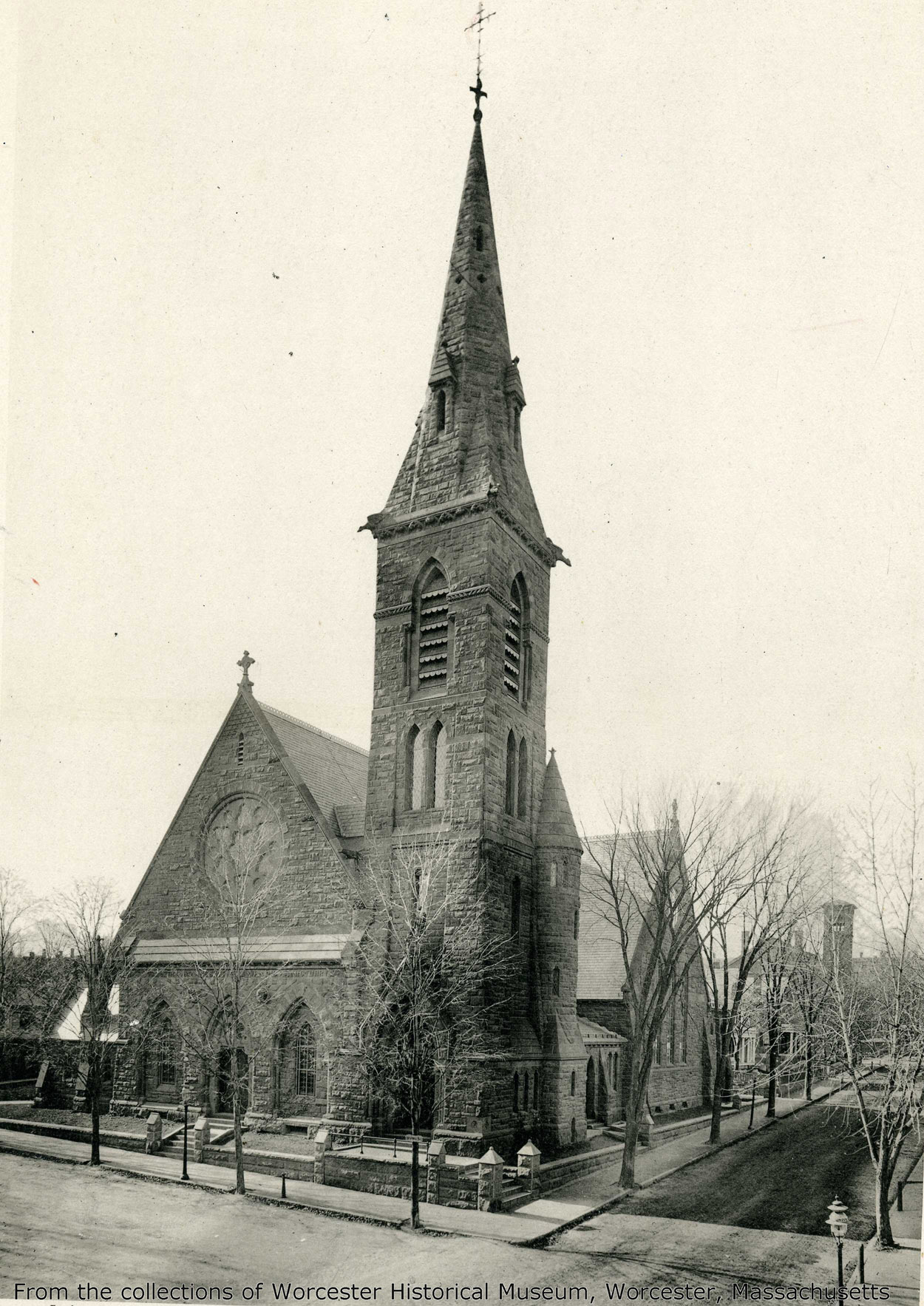

All Saints was non-symmetrical, having its tower at one corner and an entrance to the chapel on the other. The tower consisted of three levels, one being the main entrance, with the belfry on the fourth and an octagonal spire above, which tapered to a pinnacle 162 feet above the street. It was topped with an iron cross, and decorated with gargoyles at the corners of the tower where the spire begins. On the Pleasant Street side, the turret at the back corner, visible in the picture below, was a typical feature of both Gothic and Romanesque styles.

From the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum,Worcester, Massachusetts

|

||

|

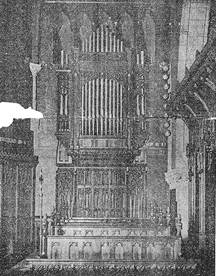

From the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts The chancel

Right: The Memorial Organ, presented to the church in 1924 in memory of William Ellis Rice, a vestryman for fifty years, by his family. It was positioned to the right of the chancel, perpendicular to the nave. |

|||

|

Worcester Evening Gazette, September, 1924

|

|||

|

|||

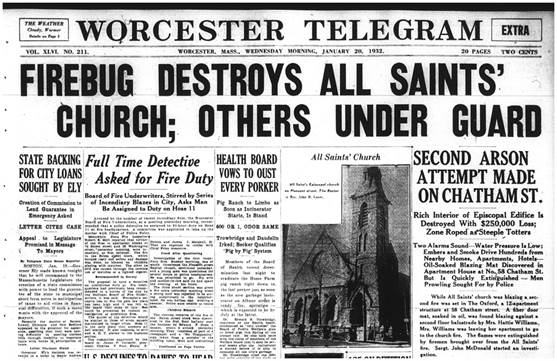

For readers of the Telegram, the morning of Wednesday, January 20, 1932, started with big headlines:

|

The WorcesterTelegram, Wednesday, January 20, 1932

While All Saints was burning, a second arson attempt was made at the “Oxford,” a 12-unit apartment house at 58 Chatham Street, but there only minor damage occurred. Prior to the All Saints fire the city’s Board of Fire Underwriters had requested a full-time detective for fire duty. |

All Saints church had been destroyed by fire overnight by an arsonist, known as the “firebug.” The “firebug” had already earned the moniker as a result of numerous other incendiary fires in the city that were presumed to have been set by the same person. A rash of fires, both successful and unsuccessful attempts, had plagued the neighborhood of the church for several days. There had been so many suspicious fires around the city over the past six months that the Telegram printed a list of 27 soon after the All Saints fire. Among the most damaging were the two fires set in December at the Bay State Hotel on Main Street, which ultimately cost the building its top two floors. It was vacant at the time and had recently been sold, and discussions were underway regarding its reopening. Article in the Gazette, continuation

|

|

That afternoon, the Gazette featured a large picture of the ruins, and devoted its full-width headline to the search for the “firebug.” An outline of the fire can be discerned in the headlines and sub-headlines within the press coverage. From the front page and page 2: 100 recruits are sworn in to aid police Mayor offers $200 reward for firebug loss estimated at $400,000 flames rise 40 feet smoke hampers work falling slate menaces pumpers work fast Washburn home haven for firemen

|

Worcester Evening Gazette, January 20, 1932 |

|

|

|

||

|

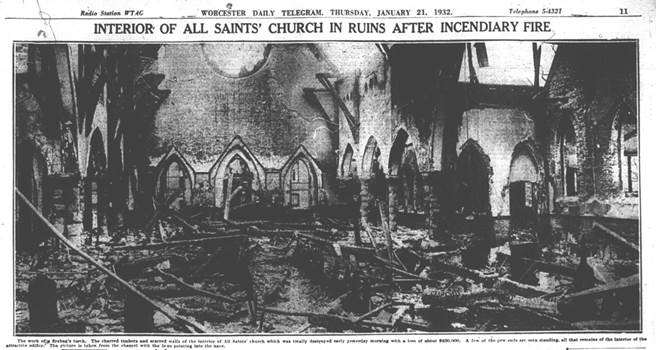

From the caption: “This picture is taken from the chancel with the lens pointing into the nave.” Under the rose window are the Irving Street main entrance and the windows on either side of it.

|

||

|

|

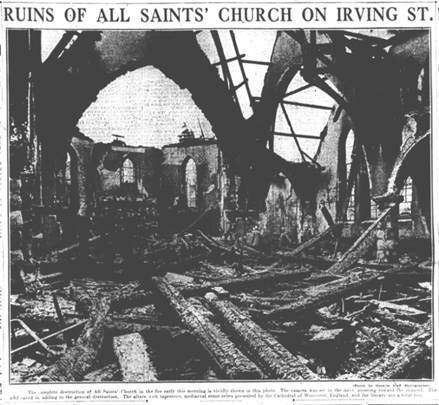

This view was toward the chancel, showing the additional destruction resulting from the collapse of that part of the roof. The memorial organ, to the right of the chancel, was completely destroyed. The caption included this:“The alters, rich tapestries, mediaeval stone relics presented by the Cathedral of Worcester, England, and the library are a total loss.” These items had been given to the church in 1877 in an act intended to cement the bonds between the Episcopal Churches of England and America. |

|

|

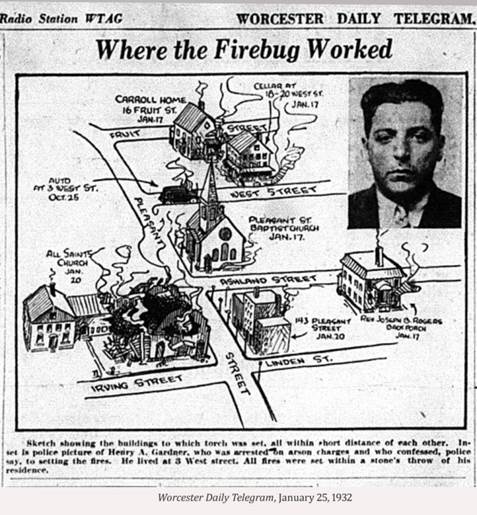

Police detectives pursued leads where they found them, and within a day or two had arrested two suspects who were being held for observation, but neither turned out to be the wanted man. Late Saturday night a footbeat officer spotted a man appearing to be about to pull a fire alarm, at Pleasant and West Streets.Upon investigation, the officer found sufficient reason to make the arrest. The man arrested was Henry A. Gardner, age 28, a resident of 3 West Street, in the middle of the area where so many attempts at arson had been made during the past week. Gardner had recently lost a laundry driving job and was now working at a speakeasy, and his wife had just given birth to a daughter. Gardner is shown in the inset of the sketch map below showing the fires he allegedly had set in the All Saints area. Police said he confessed to the All Saints fire and to several other attempts at conflagration, and that he confirmed the crimes in a walking tour with police in which he was said to have given details that only the perpetrator could have known. However, he declined to sign the confession once it had been written and typed, and that fact would lead to a challenge raised by the defense prior to the trial. Reporters were given a great deal more detailed information regarding what the police had learned from Gardner during the Sunday morning walk-around than would happen today, and the Telegram’s report of January 25 was a week before the indictment was returned by the grand jury in special session. On February 3, Gardner was charged with six counts of setting of fires. The alleged targets were four residential buildings, the Pleasant Street Baptist church, which was unsuccessful from the firebug’s standpoint, and All Saints, which was not. |

|

On January 25, the Telegram gave readers a pictorial summary of the action:

|

Automobile at 3 West St. (in October, and at Gardner’s home address) Cellar at 18-20 West St. House at 16 Fruit St. Back porch of the All Saints rectory on Ashland St. Pleasant Street Baptist Church Apartment building at 143 Pleasant St. Not mentioned but possibilities - the apartment building at 58 Chatham Street, and the two fires at the Bay State Hotel in December.

|

|

An important question on the minds of authorities and many observers was whether Gardner was a pyromaniac, and therefore presumably likely to attempt to do it again if given the chance. The trial opened Monday, February 16, when the judge declared the unsigned confession to be admissable, and it ran daily through Friday, and went to the jury on Friday. Gardner and his wife testified on Wednesday, she attempting to provide an alibi for him, and by Friday’s summary arguments there had been 30 witnesses for the prosecution and 15 for the defense.

|

||||

|

Within days of the fire the All Saints congregation was making clear its determination to stage a comeback as quickly as possible, saying the new edifice would “rise more beautiful than before.” (Telegram, Jan. 25) On February 18, during Gardner’s trial, they announced selection of architects and the builder (Telegram, Feb 19). Frohman, Robb & Little of Boston were to do the design work. Frohman was widely known for his work on churches and had been part of a team of architects who had designed the National Cathedral in Washington. The builder was to be E. J. Cross of Worcester. The plan was to begin the work within a week and to build as quickly as could be financed on the basis of an ongoing campaign to raise the needed funds. No mention of insurance was found in the accounts, but neither was there evidence that there was no insurance. The original plan was to retain the tower and the front wall, which had survived the fire. The chapel, seating 350 persons, and the parish house were completed and opened for viewing on November 1. The main part of the church, however, was not finished until 1934. As planned, the 1876 tower remained in place, but the idea of saving the stone front face of the church and incorporating it into the new structure apparently proved unworkable, for reasons unknown. As can be seen below, the new front face of the church was substantially different than the old. |

|

||

|

From the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts |

Photo by author, 2013 |

|

Side by side, the 1876 and the 1934 versions are more different than alike. The new front eliminated the rose window in favor of a triple-lancet window. The old roof came down much farther than the new one, and the new building had buttresses on either side of the entrance, while the original building had windows of equal size in those locations. The tower, the last part of the church built by the Norcross Brothers, remained intact, unchanged.

|

|

|

While the church was being rebuilt, Gardner was serving his time in Norfolk. Late in 1935, having served nearly four years, he requested parole and was given a hearing, supported by the Lt. Governor, who was quite involved in the case. Gardner’s attorney described him as being not a pyromaniac but an ordinary person who had lost his self-control while drinking to excess. As reported in the Gazette of December 19, 1935: In his plea for leniency Mr. Campbell (Gardner’s attorney) argued that Gardner was not a pyromaniac, but had set all the fires while he was on a drinking bout. Mr. Campbell said Gardner had won a considerable sum of money in a pool and that he had been unable to resist the attempt to be a “good fellow” in speakeasies, had accordingly been drinking heavily and had set fire while he was under the influence of liquor.”

The attorney was arguing that there was no reason to fear that Gardner would return to his old ways if he were paroled, and, secondarily, seeking to offset any thought of commiting Gardner to a mental facility as a pyromaniac, from which he might never return. Opposition to parole was voiced by some from the churches, including Pleasant Street Baptist, where an unsuccessful attempt had been made to set it ablaze. The pastor of All Saints argued that the burden of proof should be on the argument that Gardner was not a pyromaniac. He claimed the primary need was to protect the community as a whole, not just the church, and that if Gardner was incapable of controlling his desire for fire, then everyone was at risk. They prevailed. Gardner’s request for parole was denied. (Article in the Boston Herald regarding the flap over parole.) After serving nearly ten years, counting pre-trial incarceration, Gardner was released on probation on December 6, 1941 – the day before Pearl Harbor. He then joined the Army and served throughout the war, which can be seen as a significant contribution from Gardner, offsetting some of the costs of his past behavior. Unfortunately, however, instead of getting straightened out by his military experience, Gardner fell once again into trouble with the law. In November, 1945, he was arrested, and subsequently convicted, for a string of break-ins, mostly in the area of Union Street. In his apartment police found items identified as having been recently stolen, including jewelry, radios, cigars, and clothing, the total valued at about $1,000, plus $560 in cash. Booked on eight counts of breaking and entering and larceny, and as an ex-offender and a felon, he was sentenced to another long term in state prison, ten-to-twelve years. |

|

Although it had been open and in use since 1934, the reconstruction of the church, spread over the years as they raised the needed funds, was not completed until October, 1947, with the dedication of the new doors and fixtures. |

|

|

Worcester Evening Gazette, October 30, 1947 |

Photo by WorcesterThen, 2017 |

|

Photo by WorcesterThen, 2017 |

Photo by WorcesterThen, 2013 |

||||

|

The arches framing the entrance, called archivolts, are larger at the outside and get narrower as they approach the door, giving each one a surface facing outward that could be decorated, but in this case their fluted shapes provide the decoration. They sit upon embedded columns, and consist of pieces of what appears (to this novice) to be cast concrete, known as “cast stone,” or possibly terra cotta, placed upon each other as voussoirs of an arch, in sections of about 12-14 inches. The middle section consists of two tracks in which there are intermittent decorative elements of cast stone yielding a moderately ornate and very attractive appearance. The tympanum, the flat space above the doors, displays a carved stone likeness of the church seal, with symbols of the four evangelists at each extremity of a Latin cross surmounted by a circle. (Worcester Gazette, Oct. 30, 1947) For anyone with a hint of interest in masonry, it is well worth a visit to see it up close and real. Also recommended: save a copy of the image above (resolution: 2000 by 1500 pixels at 180 dpi, 1.1 Mb) and look at it in closer detail in your photo viewing software. It is not great photography but it is great content. |

Above – a recent view of the back and side of the church, seen from Pleasant Street. The interplay of brick and stone is a reminder of the unique history of the church building.

Right: Note the coming together of stone and brick where the tower meets the main body of the church. Lancet windows in twos, threes, and fours were continued, and stone was used in the arch for each.

|

Photo by WorcesterThen, 2013 |

|||

|

When the doors to the church were being dedicated, Gardner was serving his time at Norfolk for the break-ins,which amounted to about seven years before he was paroled in 1952 or 1953. Returning to Worcester, the only home he knew except Norfolk, he was given employment at Morgan Construction Company, he and his new wife resided on Thayer Court, and he apparently succeeded in staying out of trouble with the law. In March, 1958, Henry A. Gardner died at the age 55 of unknown cause. His death notice in the Gazette said he was given a High Mass at St. Peters and burial at St. John’s. On the whole, it appears that the church recovered better from getting torched than Gardner did from getting caught. The church, for the most part, was rebuilt within a couple of years, and the congregation never became defeated or discouraged. Gardner, on the other hand, spent about half of his adult life in prison. Although some of that time was for other crimes, his “career” started in 1932 as the “firebug.” At least he was able to spend his last few years as a free man. * * * * *

|

|

||||