|

WorcesterThen: late 19th century

Notable Arches in Worcester Architecture

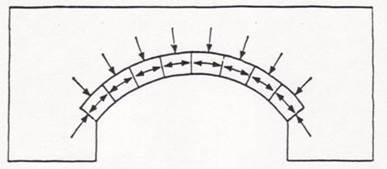

This picture illustrates the principle of the arch as a load-bearing structural element. Here workmen are making a crude vault ceiling above what formerly had been the Blackstone Canal and was now becoming a covered sewer. The vault, or barrel-shaped extended arch, was used for its capacity to support a great deal of weight above an open space, in this case the roadway that was to be built above the canal. Being underground, there was, of course, no decorative purpose. Virtually the entire story of the physical task of burying the canal is implicit in this single photograph.

|

|

|

|

The exact location is unknown (to this viewer), but it is somewhere under Harding Street, since that is what was built above the buried canal. The job was carried out between 1886 and 1896, based on the two atlases.

A map (jpg) showing the canal in 1886 (from the city atlas of 1886). The Atlas of 1896 shows Harding Street where the canal had been since 1828. |

|

The platform across the canal was moved down the line as work progressed. On it rested what appears to be half of a large wooden wheel, several feet in width, used to allow the workers to place the stones upon it. They may not always look it in this case, but the stones had to be a little bit wider at the top than at the bottom so that they would wedge into each other and no stone could fall through. The weight of the stones, plus the load placed on it from above, was transferred laterally though the adjacent stones and most (but not all) of it ultimately in the downward direction by means of bending around the arch.

Force diagram, from K. Dietrich (see Figure 15 and associated text):

|

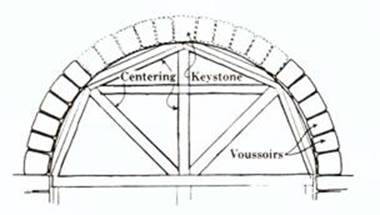

Once all the stones were set in place, the half-wheel, known as a “centering device,” could be lowered enough to make it possible to slide it out from under the stones (voussoirs) and allow them to settle and wedge into each other tightly and securely.

The device would then be pulled a few feet outward, or down the line, and the process would start again. The platform would also be moved in order to stay next to the stones being removed from the walls of the canal.

Centering device diagram, from K. Dietrich (see Figure 16 and associated text):

|

|

|

|

|

The Roman Arch Historically, the key importance of the arch was that it offered a superior way to allow for open spaces for doors and windows in heavy load-bearing walls, such as those built of stone blocks piled high with enormous weight. The only other viable means of enabling openings was the lintel - a beam above the open space thick and strong enough to manage the weight bearing down and trying to cause it to break apart in the center.

Extensive and highly productive and durable use was made of the arch by the Romans, one of the most important being the aquaduct system of the Empire, fragments of which still exist, including the Pont du Gard in southern France. |

|

|

Pont du Gard, southern France, near Nimes and Avignon |

Built in the first century, it was built as an aquaduct to supply the town of Nimes, in southern France, and it served in this capacity until the 6th century, and was later used as a toll road in the Middle Ages and the modern era. The part remaining is a World Heritage Site, stands 48 meters in height, and consists of three tiered arcades, in which there are six arches in the lower, eleven in the middle, and thirty-five in the upper. In its original form, the aquaduct was nearly 50 km in length, and in that span it fell by only twelve meters, a rate of decline calculated by the Roman engineers to be enough to guarantee that the water ran by gravity all the way to Nimes.

Ref.: http://www.avignon-et-provence.com/en/monuments/pont-gard-aqueduct

|

|

The following display of arches in Worcester (although starting with one in Holden), begins with Roman arches, which are semi-circular, and follows with gothic arches, which are pointed at the top. Photos are by WorcesterThen unless otherwise noted.

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

The Gale Free Library (Holden) |

|

|

||||||||||

|

An enlarged view of the main arch of the entrance is to the right. Other arches include the semi-circular window arch on the second floor of the tower, the partial arch on the first floor, and the triple lancet windows on the third floor. Other windows have lintels.

The Romanesque Revival architecture of the Holden library was very popular in the late 1800s.

|

The archway has 27 stones, or voussoirs, not counting the “springers” at the base of each end of the arch. The keystone is the same as the others, underscoring the fact that the keystone is just another voussoir, regardless of its shape.

Beneath the arch is a pair of double doors, with a semi-circular window above each, with small glass panes. |

|

||||||||||

|

City Hall - rear view, close-up to show greater detail

|

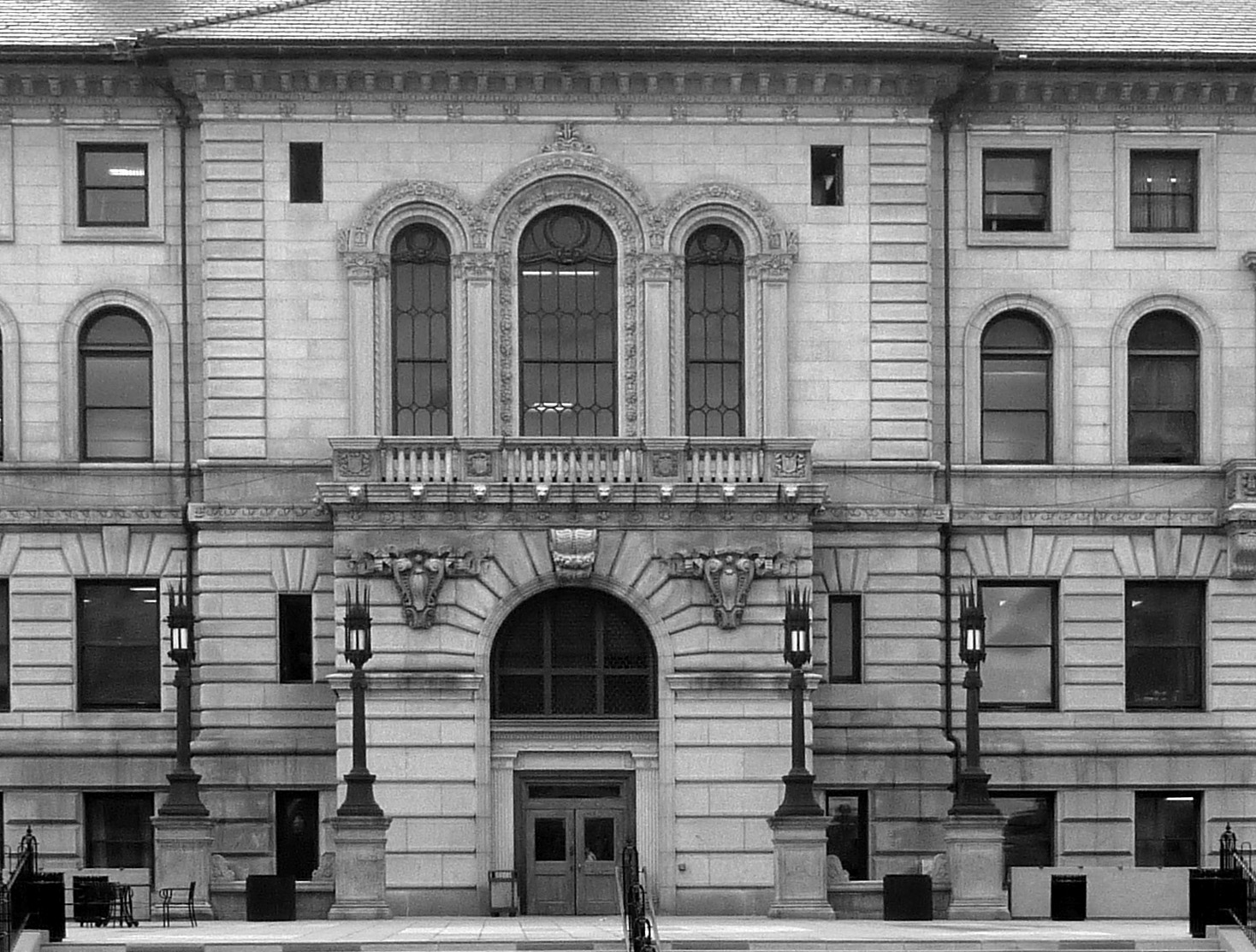

Worcester City Hall was completed in 1898. Built of granite, its massive load-bearing walls required structural arches to allow for openings for doors and windows, except in circumstances of smaller windows where lintels or careful alignment of the stone blocks could be employed to the same purpose.

It was designed by architects Peabody and Stearns of Boston, and built by the Norcross Brothers of Worcester. It can fairly be called a masterpiece of granite construction.

Four primary types of arch can be seen here: Above the balustrade over the doorway is a triple window in Italian Renaissance style, with three decorated load-bearing Roman arches.

Roman arches provide openings for windows on the third floor. Second floor windows feature 5-stone “flat arches” doing the work of arches without being in the arch shape. The doorway consists of a Roman arch of fifteen voussoirs of varying widths, with a large keystone. The tympanum above the lintel over the doors consists of screened glass panes. |

|

||||||||||

|

A highly recommended view from the top floor in the “Palace for the People of Worcester.” |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

City Hall south end, Franklin Street |

The larger arch surrounding the two smaller ones is called a relieving arch because it relieves the arches underneath it. That is, it handles the load bearing down from above, leaving only the weight of the few stones beneath the relieving arch to be handled by the arches above the windows.

The “flat arches” above the lower windows can handle only light loads because of their inefficient structure, which sends a high proportion of the load outward instead of downward. They therefore must be adequately buttressed at the ends, as is accomplished here by the amount of wall space to either side. . |

|||||||||||

|

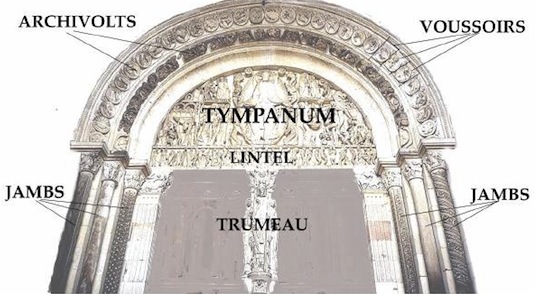

Right: An illustration from the Khan Academy online, shows the basic elements of a “high end” archway, one using archivolts and other details for an ornate and elaborate appearance.

Below: the main entrance to the Administration building of Worcester Public Schools on Irving street. Thirteen voussoirs of rough sandstone are surrounded by a cord-like shape around the arch. The tympanum consists of a fan-shaped transom light. For practical reasons, being a building in full use, it also has a modern doorway under a steel lintel. The keystone is not different from the others. There being only a single row of stones, the archivolts effect of multiple layers is absent.

|

Khan Academy online

The trumeau is a column helping to support the lintel, or for decorative purposes, typically between a pair of doors. |

|||||||||||

|

The John E. Durkin Administration Building of Worcester Public Schools, the former English, later Classical High School, built in 1892

|

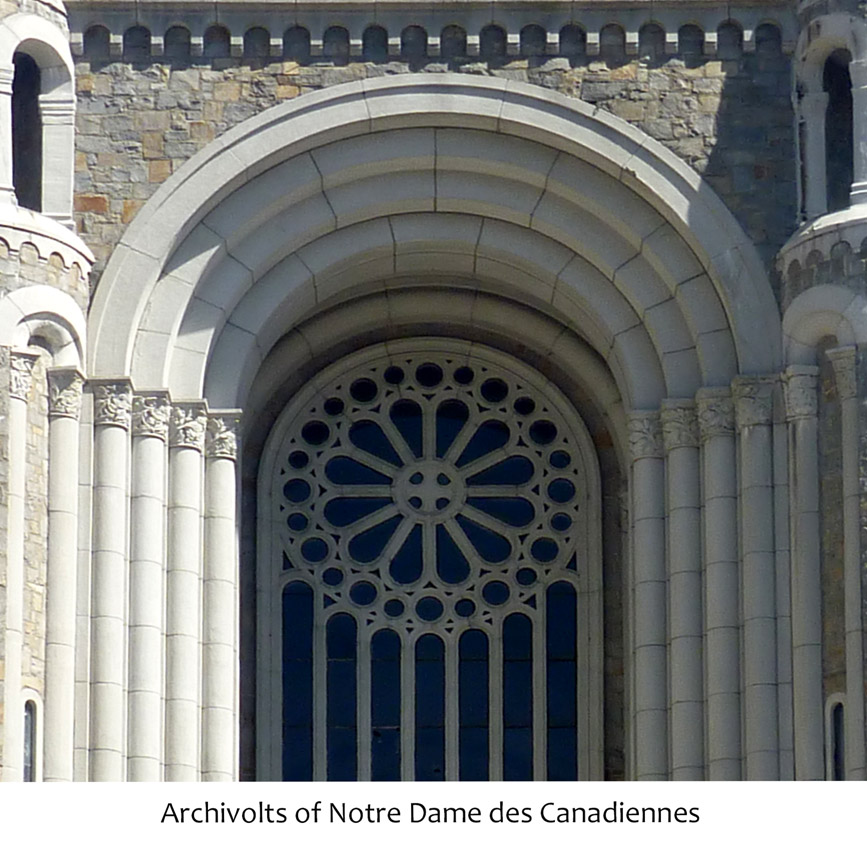

Notre Dame des Canadiennes No longer technically a church, as it was desanctified following its closure in 2007, Notre Dame nevertheless stands as one of Worcester’s architectural treasures.

The unusually high arch is made up of four archivolts -- essentially layers of a tiered archway. Left: A detail of the photo above shows four archivolts resting on Corinthian capitals at tops of embedded columns, collectively called the jamb. The archivolts appear to be placed in front of an archway surrounding the rose window, and the archway has a slightly larger radius than the inner-most archivolt. The voussoirs are made of cast concrete, each molded into two layers of the four-layer vault. Archivolts are sometimes decorated, in some instances heavily and ornately. These were not decorated, but from the distance required to view them, they offer a clean, elegant and impressive appearance. |

|||||||||||

|

The rose has twelve primary circles at the ends of “spokes,” with smaller circles between each of the twelve for a total of twenty-four. Sadly, it may be necessary in the future to change the verbs used here to the past tense, as the survival of the building at this writing is in question. |

||||||||||||

|

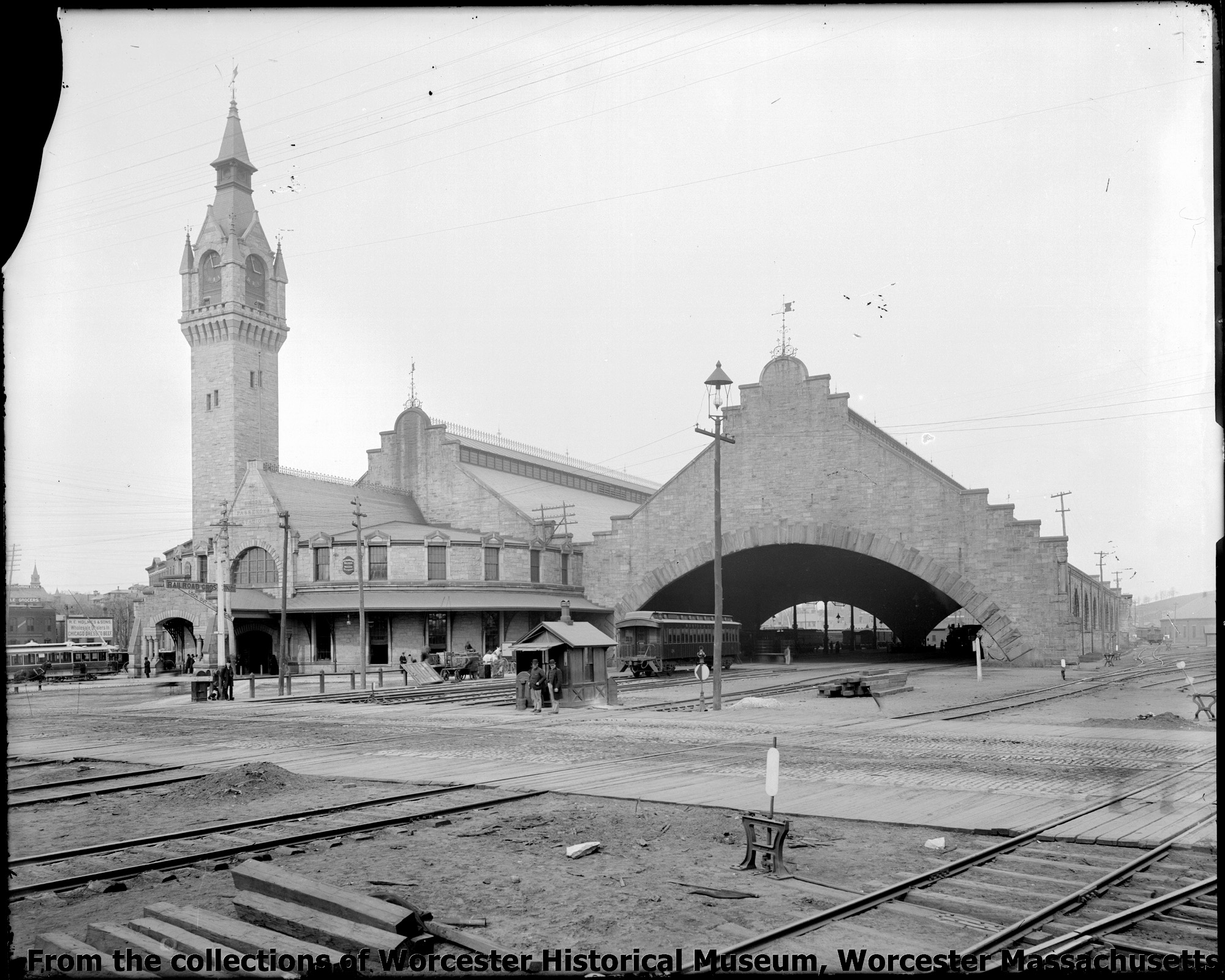

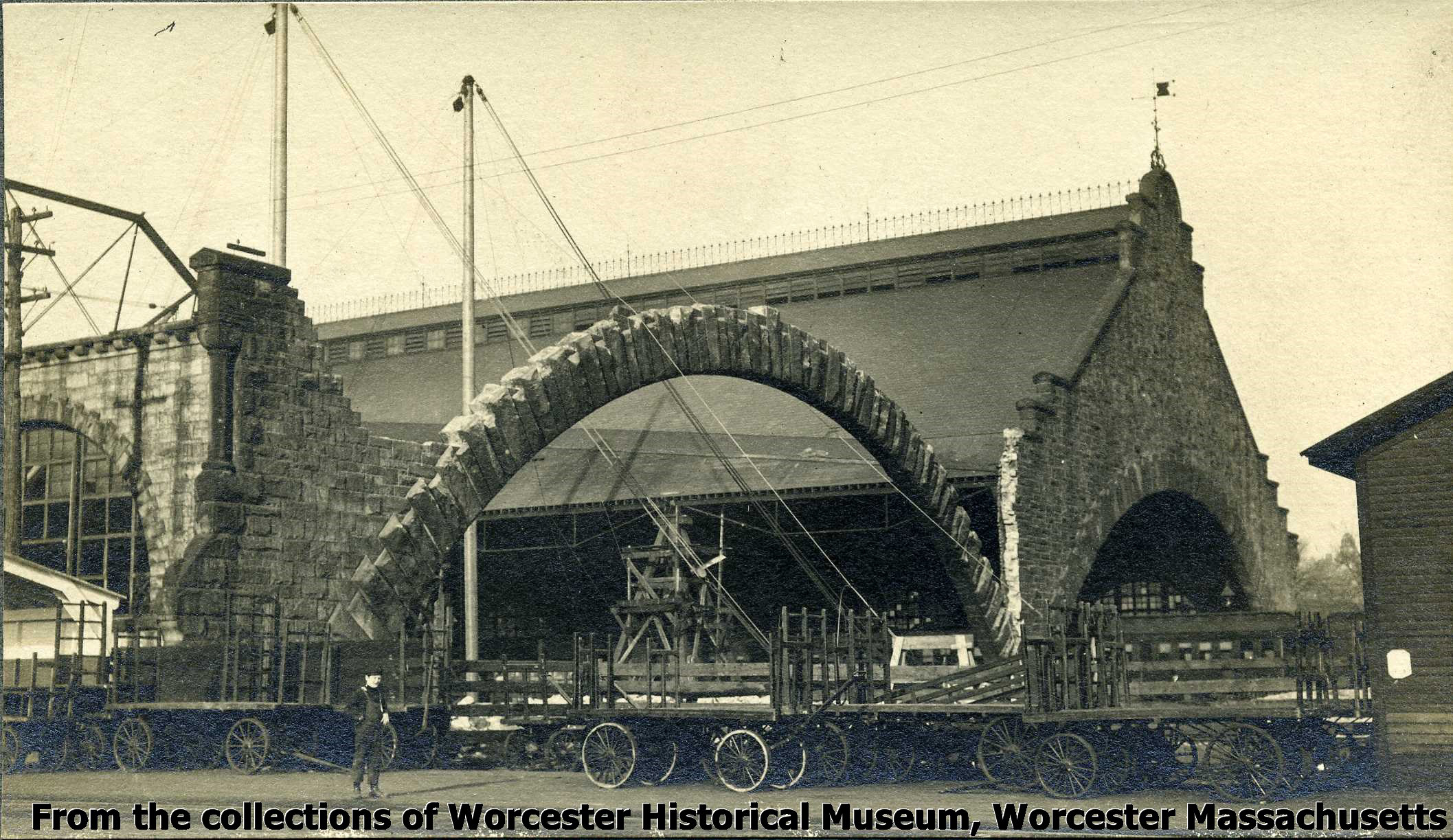

Three of Worcester greatest arches were portals of the train sheds of the original Union Station, completed in 1875 and partially demolished in 1910, the completion coming in the early 1960s. Photos shown here are from the collections of the Worcester Historical Museum.

Union Station (1875) train shed arches

|

The massive stone archways were more than 100 feet wide at ground level and the walls above them were 89 feet high at the peak. The fact that the arch consisted of less than a complete semi-circle (on the order of 120 degrees, instead of 180) created the illusion of there being not enough curvature to withstand the weight, that the arch and the wall it supported threatened to explode outward and downward. Actually it was fully capable of supporting the weight of the stone blocks above it, the key being the capacity of the anchoring granite at the base and its ability to withstand the lateral force.

According to an article in a 1910 issue of the Board of Trade publication, Worcester Magazine, there were 72 stones in the arch

This remarkable photo was taken in or about 1910 during the deconstruction of the 1875 Union Station. It shows the main portal arch of the east end of the shed, after the wall above it has been removed. The arch still presses into the base at each end, and here it stands only very temporarily with the assistance of guy wires draped across it for added security. |

|||

|

Mechanics Hall (1854)

Third floor: five large Roman-arched windows, separated by pairs of fluted columns Second floor: four triple arcade windows, plus the arch over the entrance |

Below: a detail of one of the windows.

|

|||

|

The Commerce Building, 340 Main Street, completed in 1896 as the State Mutual Building, constructed by the Norcross Brothers

|

The Central Exchange building, adjacent to Mechanics Hall, its Italian Renaissance style providing an excellent match with its neighbor.

|

|||

|

Gothic Arches in Worcester

The gothic arch features some degree of pointedness at the top, sometimes only very lightly, other times with greater authority. The difference between it and the Roman semi-circular arch was (and is) more than just design. It was also structurally important. The pointed gothic arch is more efficent in its transmission of the weight that it supports downward through its walls, toward the ground, with less lateral thrust, as if it were seeking to explode outward. The gothic arch comes closer to a parabolic shape, which is a more efficient design, although there is considerable variation in the shapes of pointed arches, some being more efficient than others. In the 11th and 12th centuries this greater efficiency of the gothic pointed arch made it possible to construct less massive stone buildings (usually churches) and to have more and larger windows to let in more light. |

||||||

|

Saint Paul’s Cathedral

The cathedral features gothic arches at every turn. Its rarely seen front, viewed from Chatham Street, presents a triple arcade, with another great arched entrance at the tower on the corner. It, too, is one of the architectural treasures of the city, and, of course, it is the Cathedral Church of the Diocese. |

A closer view of side door on High Street:

Nine voussoirs, including the wide keystone, rest on jambs of horizontal granite blocks. The tympanum is of an intricate wood and glass design above double doors of wood. |

|||||

|

A relieving arch handles the weight above it, shielding three lancet windows beneath it. |

Bethsaida Christian Center, 23 Oxford Street

Besides the arches, note the lintels over the windows of the lower floor. |

|||||

|

53 Elm Street (apartment house)

The entrance is decorated by ornamental archivolts in a mildly gothic style, with gently pointed arches, resting on jambs of narrow embedded columns. There is also a vaulted ceiling and a transom matching the glass doors. |

All Saints Protestant Episcopal Church

Cast concrete archivolts rest on embedded columns, with alternating darker and lighter sections. The tympanum is smooth stone with a symbol of the four apostles.

|

|||||

|

Presbyterian Church of Ghana, the former Union, later Chestnut Street, Congregational church

Note the gothic trefoil shapes set inside the doorway arches. The upper half of the rose window serves to transmit the weight of the stones above it around and down in the usual manner, as if the bottom half weren’t there.

|

A side view:

|

|||||

|

On balance, Worcester has a nice collection of arch structures, both Roman, which is somewhat more prevalent, and gothic. A ride around town with a camera in hand is recommended for anyone who got this far. Stephen Ressler, Understanding the World’s Greatest Structures: Science and Innovation from Antiquity to Modernity, The Great Courses, 2011 (24 half-hour lectures in DVD format) Highly recommended for anyone who likes a bit of the structural engineering that lies behind so much of the building landscape. Prof. Ressler is Professior of Civil Engineering at the U. S. Military Academy at West Point.

Closing note: No doubt there are other arches in Worcester that can be called “notable” and which could have been included in this photo essay. But enough is enough. This can be considered a start for people who find the subject interesting, and I will enjoy hearing any suggestions regarding other arches in Worcester.

|

St. Stephen’s Roman Catholic Church

Slightly pointed arches suggest a very gentle gothic touch to the design. A relieving arch shelters the three windows beneath it. |

|||||